- Home

- Michael Grant

BZRK Reloaded Page 14

BZRK Reloaded Read online

Page 14

It was not as easy as it had been on the YouTube video. But neither was it terribly hard. Ten minutes later, they were in the Toyota, and Burnofsky’s wrists were bound in electrical tape.

The phone chimed. Keats read the message. It was not from Nijinsky.

Pick up “Billy” at 18th and Q NW. Then to Stone Church. Beneath altar.

Keats gave Plath the address. “We’re picking someone up. Then, there’s a church.”

“I wonder who this Billy is.” Plath said. “The survivor?”

“I’m going to guess another sociopathic gamer who will soon be turned into a raving schizophrenic ex-gamer,” Burnofsky snarked. “Like Vincent.”

They found the corner. It was a quiet space with three apartment buildings and a couple of well-lit embassies across the road. There was no one waiting but a mixed-race kid carrying a torn black plastic garbage bag.

“Kind of young to be a homeless person,” Plath observed. She rolled down her window. “Kid. What’s your name?”

The boy was wary. He looked up and down the street. “Who you looking for?”

“Our friend sent us to pick someone up. The friend’s name is Lear.”

That was good enough for the boy. “I’m Billy. Billy the Kid.”

“Of course you are,” Burnofsky said drily.

The boy started to get into the backseat, realized it was crowded, and took the front seat instead.

“I’m Plath. That’s Keats. This is someone from the other side. A prisoner.”

Billy turned to look, and Plath took the opportunity to check out the boy in the hard greenish glow of a streetlight. He was a cute kid, she decided. And by kid she meant he was, what, three years younger than her?

She decided immediately not to do that. Not to treat him like a child.

“What’s in the bag?” Plath asked.

“Laptops and phones. And guns.”

“Laptops and phones and guns, oh my!” Burnofsky parodied.

“I grabbed it all after we got shot up,” Billy said.

“Shot up?” Keats asked, as Plath turned a hard left.

“They pretended to be cops and came in. Bang bang bang.”

Plath saw Keats’s eyes in the mirror. She asked the question on both their minds. “How did you get out alive? And have time to grab laptops?”

Billy shrugged. “Everyone was dead by then. Except the one guy I let go.”

“You let one go?” Plath could not help but be intrigued.

“It was over by then,” the kid explained. “He surrendered. Plus he pooped himself, so it didn’t seem cool to shoot him.”

“Jesus,” Burnofsky said, disgusted, but at the boy, not at the disgraced man.

“There’s the place,” Plath said, leaning down to see out of the windshield. “We’ll get out. Then I’ll go ditch the car and come back. Do you have a gun on you now, Billy?”

“Yeah.” He drew it out from under his sweatshirt. It looked absurdly large.

“If Mr Burnofsky here tries to run away will you shoot him?” “If you want me to,” Billy said.

There as an awkward and overly long pause. Finally Keats said, “Yes, that’s what we would like. If he runs or cries out, shoot him.”

“The good guys and their child soldiers,” Burnofsky said.

Not far away Helen Falkenhym Morales was writing the eulogy for her husband. She had speechwriters, but it seemed wrong to ask one of them to write a eulogy for her husband. The whole country would be watching and weeping when she read this speech.

And so far she had written the words,

I loved him. I don’t know why he had to die.

She was using a laptop, a highly secure laptop, of course— no one

hacks the president’s laptop. So she could write here, in the privacy of her office—not the Oval, that was the official office—she could write the truth or at least what she knew of the truth.

I don’t know . . .

Something happened . . .

Bad things happen . . .

Sometimes . . .

It was like bad haiku.

She swallowed Cognac. How had she ever disliked the stuff? Why did she like it so much now?

There was a bill in Congress to …something important. Very important.

Wasn’t it?

And one of the justices of the Supreme Court had been caught on tape making calls to a porn site. And that would blow up in the press.

The Iranians were. . .

The Euro . . .

Terrorism . . .

Rios . . .

I didn’t mean to hurt him.

I loved him.

I still do. I miss him. But something . . .

Backspace—erase.

There were six nanobots tapped into her optic nerve. Left eye. Getting actual visuals was hit or miss, but with multiple nanobots tapping simultaneously, sometimes you could get a pretty good picture.

Bug Man could see what she was writing.

He was in his twitcher chair, in the office space, and Jessica was standing beside him. He was showing her. She had never seen it before, never even guessed at what Bug Man did at his “job.”

“See, I’m down there inside her head,” he explained.

“What are you doing there?”

Why was he telling her this? If the Twins found out, they’d kill her. They’d flat out kill her. Or maybe not: maybe they’d make him do it.

Or maybe they’d make him rewire her even more.

Once when he was maybe six, seven, he’d heard his mother talking to her sister, his aunt, about some dude named Mills, an American. His mother and aunt had been drinking gin and tonics, not drunk but not sober, either. There had been a lot of laughing and he’d ignored it all, in the next room, paying a game. But when the laughing stopped and the conversation grew quiet, he’d put down the game and crept closer to eavesdrop.

When his mother talked about this man, this MIlls person, her voice grew heavy with emotion. It seemed like every three words there was a sigh. She had cried, and Bug Man’s aunt had comforted her and said things like, “You had him for a while, be grateful for that.”

“He loved me,” his mother had said.

“He loved you more than he loved life itself,” his aunt confirmed.

That cliché phrase had stuck with Bug Man, with Anthony Elder. More than life itself. That’s how Jessica felt about him. She loved him more than life itself. Of course that DeShawn, whoever he was, he hadn’t been made to love. No one had wired him to feel that way. Somehow it had just happened.

What would be left if he were to start tearing out the wire he had laid in Jessica’s brain? What would she see when she looked at him? What did she see now?

He looked at Jessica speculatively, watching her watch the monitor. Watching her understanding what he was and who he was. How powerful he was. How important he was.

Why was he showing her?

Why was he even here? Burnofsky had told him to go limp, to do nothing, but how could he do that? What if Morales pulled some other crazy bullshit? What if she went nuts and killed someone else?

“She’s saying she loved him.” Jessica said softly, reverently. “She must be sad. Strange, kind of, huh? I mean, the president being sad and all. Because she’s so powerful.”

Bug Man wiggled one of the probes just a little, hoping for a better resolution.

I hurt him and I hurt myself in the process, and I don’t even know why. Is that normal? Do you all understand how that happens?

Backspace—erase.

I was so determined. I knew at that moment what I had to do.

Backspace—erase.

Bug Man felt weakness in his arms. His breathing was shallow.

“I’m in trouble, Jessica,” Bug Man Anthony Elder said.

“You’re the best, Anthony,” Jessica said. It was automatic. He knew the connections that made her say it. He had laid that wire.

“They’ll kill me if this goes wrong,” he said.

“They’ll fucking kill me.”

She laid a hand on his shoulder. She leaned down to nuzzle his neck. “I can make you not so tense,” she said.

Jessica was beautiful, as beautiful as when he had first seen her, and he wanted her so badly it hurt, wanted her so badly he’d pay any price….

I loved Monte the first time I saw him

And his head made a sound like a walnut

Backspace—erase.

“Did she kill MoMo?” Jessica asked, and suddenly it was a little girl’s voice. A voice full of wonder and sweet, innocent worry.

And even as she worried she was caressing his face and neck, doing what he had programmed her to do, and something like panic rose in Bug Man’s chest, making his heart beat too fast and then too slow and he felt sick.

Oh God, how did it come to this?

That’s what the President typed. And Bug Man read it and thought, Yes, yes: How?

THIRTEEN

The Stone Church was evidently abandoned, though perhaps not so long ago. It was the sort of building that might have been considered historical, perhaps, but was small and ugly and too patched up to quite make one think of George Washington in attendance. It seemed squeezed and oppressed between a coin-op laundry and a halfway house.

Needless to say, it was not one of Washington’s tonier neighborhoods. Local residents had decorated the stone exterior with graffiti, none of it terribly original, none of it rising to the level of street art.

Keats used the tire iron from the car to pry plywood from the side door. It was a noisy job. Billy slid through the opening and pushed from the inside. Once in, Plath and Keats used the lights from their phones to find a switch. Amazingly, the switch lit up a pair of clamp lights hanging from scaffolding.

As their eyes adjusted they saw a space that was more impressive from the inside than it had been from the outside. The only window was a small, peaked, stained glass set beside the door. It was protected by plexiglass so it had not been broken, but it had been largely obscured by graffiti. Its much, much larger cousins were in a shallow dome in the ceiling. It was impossible to see the scenes clearly, but Plath counted ten panels. The moon shone through one and revealed a scene of a man in a red robe raising a knife in a threatening manner. The Ten Commandments, maybe, with “Thou shalt not kill” the only one now illuminated.

A dozen long wooden pews had been pushed aside for the scaffolding. The purpose of the scaffolding must have been to begin some restoration project, but there were cobwebs and maybe spiderwebs as well and dust everywhere, so it had been abandoned some time ago.

There was an altar, a two-step platform topped by a large rectangle decorated with lacquered tile. A wooden podium or lectern was tipped onto its side. Above the altar on the wall was a cross in rough wood, probably a fairly realistic reproduction of the original. Someone had gone to a great of trouble to climb up there and set beer cans at the ends and at the top. Two were green Rolling Rock cans and one was a dented Colt 45 Malt Liquor can.

Billy had hauled his bag inside and set it down on the altar. He searched behind it.

“We need Burnofsky tied up,” Plath said. She glanced around. There was plastic rope, neon orange. She and Keats sat Burnofsky on a folding chair and tied him to the scaffolding. The placement of the metal pipes of the scaffolding dictated an odd, asymmetrical arrangement that left one of the man’s arms stretched out and the other raised over his head. If he pulled hard enough he might just be able to pull the whole rickety structure down on himself, but they were too shaken and weary to think of any better arrangement.

“This is hardly necessary, I’m an old man,” Burnofsky said, not really putting much conviction behind it.

“Tape his mouth shut?” Keats wondered aloud.

Plath shook her head. “No. Maybe he wants to spill his guts.”

Keats grinned at her. “Seriously? Americans really say things like that? Spill his guts? That sounds very Law and Order.”

“That’s probably where I heard it,” Plath admitted.

“You two make a cute couple,” Burnofsky said drily.

“Beneath the altar,” Keats said, recalling the text from Lear. He joined Billy and the two of them tipped the altar over.

“There are stairs,” Keats said. “No light switch, though. I’m not keen to walk down there with nothing but the light from an iPhone.”

“Wait for Jin,” Plath suggested. “I’m going to see what the old man put on me.” She sounded tougher than she felt. She had come to more or less accept that nano-scale images of her own eyes or brain were simply a part of her consciousness, but traveling out over her own skin still held terrors for her. She would have liked to take a good long shower first at least. You never knew what microscopic monstrosities you might encounter.

“I can do it,” Keats offered, stepping back from the altar.

Plath shook her head. “Bad enough I’ve got you in my brain. I don’t need you crawling over my epidermis.”

“Then I’ll update Lear and Jin,” Keats said.

Plath motored her two nanobots around her own eye. From the massive Golden Gate Bridge cable–size nerve onto the eyeball itself.

The back side of the eye was very different than the front. If the front was a sort of eerie frozen lake with an awful black pit in the center surrounded by stretched chewing gum muscles, the back was an alien landscape of seemingly impossible constructions formed by nerves and muscles and surface veins like tree roots.

Or perhaps the veins were more like pythons. She could see the shape of the blood cells that surged and slowed, surged and slowed with each heartbeat. The platelets were a sort of slurry in the larger veins, then branched off into smaller veins, and capillaries where they piled up, single file like impatient children pushing in line.

It was impossible at this scale to see blood as liquid. They were objects, each cell tiny but distinguishable. Wet red stones being forced through a pale sausage casing.

Then there were the muscles, giant bundles of rubber bands that fused into eyeball and jerked incessantly, though at the nano level she didn’t so much feel the motion as see it when the slanting rubber bands would thicken in contraction, stretch out in release, endlessly adjusting as though somewhere there must be an absolutely perfect angle for the eye and the muscles were determined to find it. Plath’s biots came around into the light on the lower edge. Bottom eyelids move less and could be more easily climbed than the swift-rushing upper eyelid. The edge of the lid was a shoreline of tall bluffs topped by scaly, curving palm trees. Eyelashes.

The lower lid jerked and the line of palm trees shot toward her. The lid and lashes rushed with startling speed, slid over her and blotted out the feeble light. She jumped both of her biots simultaneously and caught the wet membrane above.

This movement she felt, the impact, as the eyelid suddenly reversed direction and swept her back and away. Now clinging upside down to the lid, the eyeball itself swept by above/beneath her.

She steeled herself for the next part as she climbed—upside down, but in the nano up and down mattered very little—to emerge in the line of eyelashes. There, face-to-face with her, a demodex.

In the m-sub—micro-subjective—the demodex was almost as large as she was. Its face was a crude spider’s mouth and two utterly blank Hello Kitty! button eyes. God only knew what it saw—surely not much. The demodex was calmly munching a dead skin cell that looked rather like a fallen leaf after a rain.

The demodex did not respond to her presence—nothing in a demodex’s evolution had prepared it for this—it just kept eating.

The shortest way forward was to clamber straight over the mite. With a shudder Plath sent her biots scampering across, through the scaly trees, and out onto broken ground.

In and out of desert ravines, past scattered balls of pollen in half a dozen different colors and shapes. The pollen grains looked oddly like an assortment of footballs and soccer balls left carelessly on a playing field.

On

to the cheek. Here the skin was smooth—no more ravines. Those would come no doubt with age—but for now her skin was a carpet of leaves, dead cells drifted onto a living substrata. As she watched a handful of dead cells broke loose and fluttered away.

The biots could not see distances well. So Plath knew that the massive, Everest-size mountain off in the distance was her nose, but she wouldn’t easily have recognized it as such.

“Ahh, what the hell?” she cried. A long, low, dark berm was directly ahead. The rough blanket of skin cells suddenly rose, looking like some kind of burial mound, like some dark tumor.

“Freckle,” she said, relieved to realize what it was.

“I like your freckles,” Burnofsky said up in the world. “I’m sure your English friend admires them as well.”

She skirted the freckle and saw more of them across the landscape ahead.

As she neared her lip the fine hairs appeared, much smaller than eyelashes, less like scaly palm trees and more like widely scattered stalks of wheat. It was impossible to avoid the sensation that she was racing across a fantasy landscape, something out of a science-fiction movie. And while that was happening she was accepting a can of soda from Billy, who had been sent to the 7-Eleven down the block to bring in supplies.

Her biots saw the soda can—an unimaginably large object, a Hindenburg rendered in lurid red—arise from the horizon and seemingly crash into the landscape ahead.

The Coke went down her throat.

“There’s a slight scratch where he brushed against you, I think,” Keats said, up in the world. He was looking closely at her neck. “You’re sweating. Don’t move.”

She turned her biots and saw the wall of water racing toward her. It was a glistening ball, more like a water balloon rolling down a hill than a drop of water, solid rather than liquid.

She cut sideways sharply but just then a pillar came stabbing down out of the sky.

In the macro she saw Keats’s finger. He touched the drop of sweat. He was very close to her, which may have been why she was sweating, or maybe it was that she hadn’t taken off her coat and it was humid in the church.

Fear

Fear Plague

Plague BZRK: Apocalypse

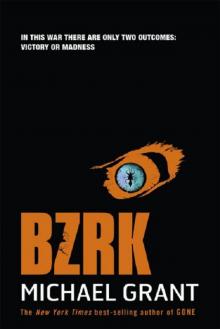

BZRK: Apocalypse Bzrk

Bzrk Love Sucks and Then You Die

Love Sucks and Then You Die Silver Stars

Silver Stars The Key

The Key Front Lines

Front Lines BZRK Origins

BZRK Origins Monster

Monster Gone

Gone The Snake

The Snake The Power

The Power Hunger

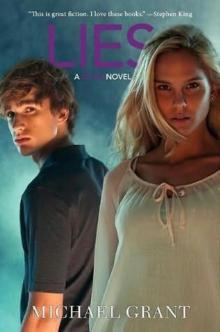

Hunger Lies

Lies A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Messenger of Fear

Messenger of Fear Eve & Adam

Eve & Adam The Trap

The Trap Light

Light An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam

An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam The Call

The Call Hero

Hero Soldier Girls in Action

Soldier Girls in Action Purple Hearts

Purple Hearts The Tattooed Heart

The Tattooed Heart The Fall of the Roman Empire

The Fall of the Roman Empire BZRK Reloaded

BZRK Reloaded Messenger of Fear Novella #1

Messenger of Fear Novella #1 The Magnificent 12

The Magnificent 12 Fear: A Gone Novel

Fear: A Gone Novel Villain

Villain Manhattan

Manhattan Eve and Adam

Eve and Adam Plague: A Gone Novel

Plague: A Gone Novel Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises In the Time of Famine

In the Time of Famine Hunger_A Gone Novel

Hunger_A Gone Novel Lies g-3

Lies g-3