- Home

- Michael Grant

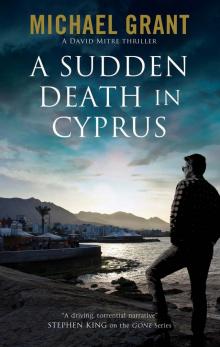

A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Read online

Contents

Cover

A Selection of Titles by Michael Grant

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

A Selection of Titles by Michael Grant

Gone Series

GONE

HUNGER

LIES

PLAGUE

FEAR

LIGHT

VILLAIN

A David Mitre Thriller

A SUDDEN DEATH IN CYPRUS *

* available from Severn House

A SUDDEN DEATH IN CYPRUS

Michael Grant

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

First published in Great Britain 2018 by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD of

Eardley House, 4 Uxbridge Street, London W8 7SY.

First published in the USA 2019 by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS of

110 East 59th Street, New York, N.Y. 10022

This eBook edition first published in 2018 by Severn House Digital

an imprint of Severn House Publishers Limited

Trade paperback edition first published

in Great Britain and the USA 2019 by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD.

Copyright © 2018 by Michael Grant.

The right of Michael Grant to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7278-8835-8 (cased)

ISBN-13: 978-1-84751-960-3 (trade paper)

ISBN-13: 978-1-4483-0170-6 (e-book)

Except where actual historical events and characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to living persons is purely coincidental.

This ebook produced by

Palimpsest Book Production Limited,

Falkirk, Stirlingshire, Scotland

For Katherine (K.A.) Applegate, the real girl in the window.

ONE

At any given moment there are about two hundred thousand fugitives from American justice and about forty thousand fugitives from Her Majesty’s justice, running free in the world. Two of those fugitives, one from each nation, were within fifty yards of each other on the beach a bit north of Paphos, on the Mediterranean island nation of Cyprus.

One was about to die. The other was not.

I was the ‘not.’

I wasn’t strictly on the beach, rather I was on a stool beside the tiki bar drinking Keo, the execrable local beer, and wondering if the immediate vicinity was sufficiently sparsely-populated that I could light a cigar without causing a riot. Cypriots probably wouldn’t care, but this was not a Cypriot beach, it was a tourist and expat beach. The Paphos region at the extreme western edge of Cyprus is home to thousands of expats, mostly Brits, but with Russians, Germans, Israelis, Lebanese, various Balkan types, Scandinavians and the occasional American thrown in for good measure.

The British fugitive, the one who was about to be subtracted, was a woman, perhaps forty-five, with forgettable brown hair and shoulders that glowed faintly pink, suggesting a failure of sunblock. She lay on a blue-and-white-striped canvas chaise longue, facing the sea, her back to me. Her chaise was tilted at just the right angle to aim her cleavage in my general direction, though I doubt it was intentional, but as I had already seen a fair bit of the Mediterranean, and all of the beach, and there was nothing more compelling presenting itself, I spent some time contemplating those sunburned swells.

She was not on sand – there are precious few sand beaches on Cyprus, and the Turks have the best of them – but on the grass just before the sea wall which left her two or three feet above the narrow, pebbly strand below. Her chaise was in a row of identical chairs and she was reading a book on actual paper. A bottle of local white wine – rather better than the beer – rested in a bucket at her elbow. Like approximately all women over the age of bikini, she wore a broad straw hat and whenever she looked up, the back of her hat came down and blocked my view. When she looked back down at the book, I saw plump pink breasts and a blue one-piece bathing suit and legs that probably looked better without perspective turning them into tapers ending in tiny sandals.

‘Peek-a-boob,’ I said to Theodoros, the barman, as the hat brim lifted again.

Theodoros – twenty-something, dark bed head, dark bedroom eyes, with competent but accented English and a degree in chemistry – stopped polishing a glass and stared at me.

I grinned at him. ‘See, it’s peek-a-boob because—’

‘I understand, Mr Mitre. I’m just not going to encourage you with a phony laugh.’

I couldn’t see the book the woman was reading, but my few needy glimpses of the cover assured me that it was not one of mine. I write. Now. Didn’t always write, but now I write and have produced five reasonably well-received, and moderately successful – or perhaps not entirely unsuccessful – mystery novels, all set in the city of New Midlands, a fictional locale located almost exactly where you’d find Chicago. New Midlands: Chicago, but with far more rich and attractive people committing far more complex and fascinating crimes than actual criminals have the energy, imagination or resources to pull off.

‘I’ve heard you phony-laugh for customers before, Theo,’ I said.

‘My contempt for that particular … jape … is evidence of my underlying respect for you, Mr Mitre.’

I liked Theodoros because he spoke English well enough to get a joke. Everyone on Cyprus speaks English, or thinks they do, but Greek to English is a big leap and few manage it. There aren’t many bartenders who can drop jape into conversation.

‘Well, grab me another beer, Theo, and I’ll come up with a more sophisticated witticism.’

My name is David Mitre, at present. I’ve gone through a few names, including the insufferable ‘Carter Cannon,’ which was ridiculous, like a superhero’s alliterative secret identity. I’ve also been Martin, Alex, Frank, Thomas, Michael and now, David. The David Mitre Wikipedia page uses the word ‘reclusive’ three times. There’s an author headshot but it doesn’t

take much Google-fu to discover that it’s a stock photo. The model looks a bit like me, but not really. For one thing, Mr Stock Photo grows a much more convincing beard than I could ever manage; I stay clean-shaven. Mr Stock Photo also doesn’t quite capture the subtle fight-or-flight paranoia that radiates from me.

Here is why I kept focusing on the woman with the cleavage: because of the way she was looking around. People generally do look around a bit when they’re on a pleasant green verge beside sparkling water, but there are different ways of doing it. A person waiting on someone will look and then check their watch or phone. A person enjoying scenery will let their gaze wander, left, right, up, right again, maybe whip out that phone for a picture. But she wasn’t looking for a waiter – she had barely touched her wine. And she wasn’t looking for a toilet, she’d gone ten minutes earlier.

Ms Cleavage – probably not her real name – was looking around in a more methodical way. She would read her book for almost exactly two minutes, then scan left to right. All the way left, all the way right.

If I were a character in my own fiction, I might claim to have pulled a Sherlock and immediately deduced that she was one of the fugitive tribe in which I hold membership. But that would be stretching a point. I was looking at her because something about the way she scanned the world around her bothered me, and I have no better explanation than that. Just something off.

I didn’t really sense anything unusual was about to happen until I caught sight of the waiter, entering stage left.

I, too, look around more than strictly necessary. I had discovered Fugitive Vision soon after jumping bail in Reno, Nevada nineteen years ago. How we look at the world – physically, not metaphorically – is very much a matter of culture, and westerners tend to focus about ten to twenty yards out, occasionally widening to take in context, but mostly folks look to recognize a face, a face that is in their immediate vicinity. Fugitive Vision pushes out further so you focus about a hundred yards out, looking for faces the instant they are close enough to be recognized. Like submarine warfare, it’s all about seeing before you are seen.

The waiter was a black African, Somali maybe, presumably one of the luckier refugees to come ashore in this refugee-besieged nation, and had caught my eye not because he was anyone who might recognize me but because of the way he moved. Among the many jobs I’ve held in my forty-something years is waiter. I know how waiters move and it wasn’t like this. The waiter had a drinks tray on his left palm – so far so good – but he steadied the wine bottle upon it with his right hand. And the bottle itself was positioned toward the edge. The outer edge. Which, as any half-bright server would know, was madness. Or at least awkwardness.

There are two ways for a waiter to carry a wine bottle: in the center of the tray, or in his hand with the tray folded under his arm.

Then there was the way he walked, loping, swaying a bit, side to side. Watch a waiter move sometime: it’s left in front of right in front of left. And there will be a swivel to the hips useful for cutting close to tables and chairs. This guy moved like Jar-Jar Binks, or the guy from the Grateful Dead ‘Truckin’’ logo. No wonder he couldn’t balance a bottle.

An impressive yacht, practically a pocket-sized cruise ship glided by like an iceberg passing by on a conveyor belt. Tan young women in small bathing suits waved at us. Theodoros brought me the beer.

‘You’ve got to start stocking better beer, Theo.’

‘I have Peroni.’

‘Like I said.’

Ms Cleavage looked up as the vendor’s shadow fell over her. I saw her shake her head, ‘no, not for me,’ and return her gaze to the book.

The waiter knelt, set the tray carefully on the grass and reached into his pocket for his wine opener.

Then I saw the knife.

It was a serious knife with a double-edged, seven-inch, blued blade. This was not a pocketknife or something lifted from the kitchen, this was a professional’s tool. The vendor bent over Ms Cleavage, too close, as though he was speaking to her in a whisper. She looked up again, annoyed now. I caught a glimpse of her face reflected in his mirrored shades.

He slapped his left hand over her mouth. His right hand went behind the chaise longue and stabbed the blade right through the blue-and-white-striped canvas.

The blade entered around what I guessed would be the latissimus dorsi. He worked the knife inside her, pushing down on the leather-wrapped handle to lever the blade upward and slice into her lungs, then pulling upward, muscles straining, to force the tip down toward her liver. Then he twisted the knife in place, widening the entry wound. This all took maybe four seconds.

The woman jerked. Spasmed. And again. And a kick that sent one sandal flying.

But it was over quickly. The African might not be much use as a waiter but he knew his business with a knife.

Despite his twisting, he had to get his body weight into the job of pulling the knife out and when he did blood gushed from the tear in the fabric, splashing red on the grass. Christmas colors, red and green.

I shot a look at Theodoros. He had not seen. No one had, not yet.

I got up from my stool, beer in hand, said, ‘Put it on my tab, I have an appointment.’

Theodoros nodded, preoccupied with new customers, and I walked directly away, up toward the resort hotel. I was on the terrace when the first scream rose behind me. I put on a frown and looked around in a perfunctory, befuddled sort of way for the benefit of any possible cameras, shrugged and went on through to the hotel’s lower level, up the stairs to the main lobby and out to my car.

I got in and drove away keeping to the speed limit not for fear of traffic cops but because it’s hard to concentrate when you’re shaking and fighting the urge to vomit.

When the killer had pulled the knife out it was like slicing a wineskin. That was not a memory I wished to savor, but imagination – so very useful in my current profession as writer – now supplied lurid and detailed mental images of internal organs crudely butchered. I’d been too far away to hear anything but a slight gasp, but ever-helpful imagination provided sound effects of cleavers on rump roasts.

I have not lived a sheltered life. I’ve seen people in the act of being killed. It’s not a good thing to see, but I had more immediate issues to deal with. There’s the old line from Casablanca. ‘Round up the usual suspects.’ It doesn’t matter what the crime is, a fugitive is automatically a ‘usual suspect’ and my passport, which passed muster at border crossings, could start raising red flags if cops really started looking.

So, I drove off, congratulating myself on quick thinking, regretting only the excuse I had given. An appointment? That could come back to haunt me.

When I got back to my rented hillside villa I poured myself half a tumbler of Talisker and drank it down as my nerves jumped and twitched.

We all see murders on TV and in movies or read about it in books; it’s a very different thing when you see it in real life. There is a terrible wrongness to it, something you feel in your soul – if you believe in such things as souls.

I told myself it was someone else’s tragedy, not mine. I reminded myself that I am not superstitious and that it was in no way an omen or a warning. I told myself it really didn’t matter and had nothing at all to do with me.

And it didn’t. Until it did.

TWO

My rented villa had come with an unexpected nuisance: the lower floor was rented separately. I had learned this only upon moving in and my landlady, Dame Stella Weedon, a Brit expat, tried to la-di-da it away as some sort of local custom. But the reality was more sinister. There was a movie shooting on the island, a rom-com of some sort involving George Selkirk, then fifty-one years old, and an unknown French actress half his age named Minette. Just Minette. In the world of clickbait, they were known as Kirkette because the alternatives were Morge, Selette and Georgette.

The downstairs renter was not Minette or George, let alone Kirkette; the downstairs renter was Chante Mokrani. Chante – pronounced

‘shont’ unless you wanted her to punch you in the neck – was personal assistant to Minette, and Dame Stella would have given her last sleeve of Hobnobs to get either part or all of Kirkette to attend one of her frequent parties.

My first encounter with Chante had come when I marched downstairs to ask her to turn down her music.

‘Hi. I’m the guy who lives upstairs,’ I said by way of introduction.

My first impression of her was that her first impression of me was unfavorable. It was dislike at first sight. She disliked everything about me, every detail, as she looked me up and down and back up again. It wasn’t actual hate, it was more a sort of disappointment, as if I was the birthday present she really did not want or a dish she had not ordered.

This was disturbing to me. I’m a good-looking guy. I’m not George Selkirk, maybe, but women simply do not turn their noses up at me on first sight. Usually they don’t actively dislike me until I’ve emptied one or more of their bank accounts. Sometimes not even then.

‘Yes?’ Chante Mokrani said.

‘The music. I was wondering if you could turn it down.’

‘Why?’

‘Why?’

‘Yes. Why?’

So, right away I knew she wasn’t British. A Brit would have apologized and turned it off entirely. He would have called me a wanker as soon as I was out of earshot, but first he’d have turned it off.

Chante was on the elfin side, not tall, with stylishly-cut, vaguely punkish black hair, several piercings, moderate gauges in her ears, angry dark eyes and a thin-lipped mouth which did not raise expectations of warm smiles.

‘Because it is very loud,’ I explained. I added hand gestures, pointing at my ears with both index fingers.

She shook her head. ‘No, it is not very loud. It is fado, not rock music. Fado.’

‘Yes, I know it’s fado—’

‘Tânia Oleiro.’

‘I’m just not that crazy about Portuguese blues cranked up to eleven.’

That made her blink. She had not expected me to recognize fado, the mournful Portuguese version of blues, full of lost loves and, presumably, complaints about Spaniards.

Fear

Fear Plague

Plague BZRK: Apocalypse

BZRK: Apocalypse Bzrk

Bzrk Love Sucks and Then You Die

Love Sucks and Then You Die Silver Stars

Silver Stars The Key

The Key Front Lines

Front Lines BZRK Origins

BZRK Origins Monster

Monster Gone

Gone The Snake

The Snake The Power

The Power Hunger

Hunger Lies

Lies A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Messenger of Fear

Messenger of Fear Eve & Adam

Eve & Adam The Trap

The Trap Light

Light An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam

An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam The Call

The Call Hero

Hero Soldier Girls in Action

Soldier Girls in Action Purple Hearts

Purple Hearts The Tattooed Heart

The Tattooed Heart The Fall of the Roman Empire

The Fall of the Roman Empire BZRK Reloaded

BZRK Reloaded Messenger of Fear Novella #1

Messenger of Fear Novella #1 The Magnificent 12

The Magnificent 12 Fear: A Gone Novel

Fear: A Gone Novel Villain

Villain Manhattan

Manhattan Eve and Adam

Eve and Adam Plague: A Gone Novel

Plague: A Gone Novel Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises In the Time of Famine

In the Time of Famine Hunger_A Gone Novel

Hunger_A Gone Novel Lies g-3

Lies g-3