- Home

- Michael Grant

Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises Read online

FERGIE RISES

How Britain’s Greatest Football Manager

Was Made At Aberdeen

MICHAEL GRANT

CONTENTS

Preface

1. ‘Cup finals are too big for some players’

2. A discreet call to the Jolly Rodger

3. Rescuing Alex Ferguson

4. ‘Be arrogant, get at their bloody throats’

5. The Cull of the ‘Westhill Willie-biters’

6. ‘Doug Rougvie Is Innocent’

7. ‘You’re too quiet’

8. Liverpool

9. Crime and punishment under the Beach End

10. Ipswich fall to the Jock Bastards

11. The Glasgow press, those hated characters

12. The Old Firm: ‘We didn’t like Aberdeen, they didn’t like us’

13. ‘Where’s Hungary from Albania?’ That’s not an easy question with twenty minutes to go

14. Real Madrid

15. The hairdryer and the baseball bat

16. European Team of the Year

17. What’ll it be, digestives or chocolate biscuits?

18. ‘This season’s target is two trophies…minimum’

19. ‘It’s Ibrox, don’t be scoring five, six or seven against them’

20. This isn’t the real Fergie

21. Souness

22. A death in the family

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Index

Photographs

Copyright

PREFACE

The problem with Sir Alex Ferguson is that his mind games continue indefinitely, and they make unintended victims of the clubs and the supporters who idolise him. Wherever he works, he conjures the illusion that the sun will never set. Then he leaves, the world turns, and his clubs fall back into shadow.

All four of the football clubs he managed in his thirty-nine-year career look back on their period of ‘Fergie time’ as the very best of days. More than a quarter of a century after he last managed a Scottish team, East Stirlingshire, St Mirren and Aberdeen continue to cherish their fading memories, and their ageing fans yearn for a return to the way things were under Ferguson. Even Manchester United have felt the sting of his departure in 2013. United’s global army of supporters may have to resign itself to the truth that the club may never again be so relentlessly successful. So far, Ferguson’s unwanted legacy has always been anti-climax and decline for those he leaves behind.

Nowhere has the chill been more keenly felt than at Aberdeen, because nowhere else has his influence raised a team to such unprecedented heights. For seventy-five years that modest club on Scotland’s north-east coast had been decent and respected, rising occasionally to make a brief challenge to the Old Firm, only to settle back into its accustomed place in Scottish football. Before Ferguson they won one league title and four cups. And then the tornado struck. In his eight and a half years there, Aberdeen won ten trophies.

Between 1978 and 1986 he turned the Dons into one of the most formidable forces the Scottish game has seen, and in 1983 one of the greatest to leave these shores and win a European final. For more than 125 years, football in Scotland has been a tennis rally, its main honours rebounding back and forth between Rangers and Celtic. Ferguson changed that, leading Aberdeen as the senior partner in a ‘New Firm’ with Dundee United. The passing of time has only made his impact shine forth all the more vividly in the record books. Ferguson’s Aberdeen remain the only club to challenge and topple the Old Firm over a concerted period.

He lifted Aberdeen, and the 1983 European Cup Winners’ Cup final defeat of Real Madrid in Gothenburg elevated him. That was the towering achievement that made his a world-renowned name. When he took his first training session on an Aberdeen public park on 17 July 1978, he began a narrative which would continue beyond Scottish football and find its ultimate fulfilment at Manchester United. Aberdeen was the blueprint. He faced down early disruption and opposition from troublesome players at Aberdeen, as he did at United. There were trophyless early seasons before the floodgates opened for Aberdeen, as there were for United. He imposed an iron will on Pittodrie, as he would at Old Trafford. He built a side around an exceptional leader, Willie Miller, as he did later with Bryan Robson and Roy Keane. He forgave an errant talisman, Steve Archibald, as he did Eric Cantona. He knocked Rangers and Celtic ‘off their fucking perch’, as he did Liverpool. Crucially, he strived to create an aura around Aberdeen, as he would around United. Aberdeen lost their first two cup finals under Ferguson, and then won all of their subsequent six. That was not entirely down to being the better team on the day; part of it was because Ferguson had learned how to prey on opponents’ doubts and vulnerabilities.

His post-match Hampden rant about Aberdeen’s ‘disgrace’ of a performance in the 1983 Scottish Cup final, when they beat Rangers, was an iconic incident which captured the energy, hunger, temper and rawness of the young Alex Ferguson. In an official history to celebrate the club’s centenary in 2003, he told author Jack Webster: ‘There is no doubt that Aberdeen made me as a manager.’ That was no hollow platitude, but the truth goes further: his years with Aberdeen made him as a man. Between 1978 and 1986 he lost his father and he lost his mentor, Jock Stein. He also won his first major honours at home and in Europe, saw his sons grow up, and became one of the most provocative, admired and recognisable figures in Scottish life. The transformation was profound: from being not good enough for St Mirren, to good enough for Manchester United.

From the start, my intention was that Fergie Rises would offer a fresh and deeper perspective on Alex Ferguson’s time at Aberdeen. I interviewed every member of the Gothenburg team, and dozens of others who served under him, including his three assistant managers and other club staff. It was rewarding to sit with fine players like Dom Sullivan, Ian Fleming, Jim Leighton, Gordon Strachan, Mark McGhee and Eric Black, all of whom had their problems with Ferguson, either at Aberdeen or subsequently, and all of whom gave their views candidly. Whether favoured or not, these men relayed their personal ‘hairdryer’ anecdotes like badges of honour. It was soon clear that working with Ferguson was a blast in more ways than one. What came through clearly was what a laugh they all had. Ferguson was controlling, dictatorial, moody and inconsistent, but he was often cracking good fun.

No previous book has been devoted entirely to that eight-and-a-half-year period, and none has interviewed players from Rangers, Celtic, Dundee United, Hearts and others to ask how it was to play against those Aberdeen teams. Prominent Old Firm figures, such as Ally McCoist, Charlie Nicholas and Davie Provan, gave insights into Ferguson’s competitiveness and cunning. They were front-line eyewitnesses to–and sometimes casualties of–those bloody battles at Ibrox, Parkhead, Pittodrie and Hampden. And, perhaps surprisingly, they spoke approvingly of Aberdeen’s nasty streak.

There is testimony from European opponents within these pages, too. ‘They were a really difficult team to play. Tough bastards,’ said Terry Butcher, a member of the Ipswich team who were Uefa Cup holders until Aberdeen knocked them out. Players in the Bayern Munich and Real Madrid sides laid low by Ferguson’s Aberdeen spoke as well. The great Karl-Heinz Rummenigge remembered, thirty years on, how the Dons ‘fought like hell, to the last second’. Referees and journalists also shared their tales. There were exceptions, but the overall feeling was warmth and fondness towards the man, if not always his methods. What became clear was just how relentlessly eventful it all was: cup finals, European adventures, broken tea cups, fallings-out, red cards, and always the threat of that ‘hairdryer’ should anyone step out of line.

Occasionally colleagues would ask if Ferguson himself had contributed. But those who have written about him, or about Aberdeen, are well aware that he now

declines all requests to be involved with books about himself or his clubs, unless they are official publications. I had never intended to ask. I had interviewed him in the past and wrote about him at length for a previous book, The Management: Scotland’s Great Football Bosses. Besides, Ferguson’s version of events is already so well-known, thanks to his 1985 account of the Aberdeen years, A Light in the North, and his more revealing 1999 autobiography, Managing My Life. A time comes when even the sharpest mind has no more nuggets left to mine. What others had to say would be more revealing now.

For those of us who follow Aberdeen, there is a temptation to recoil from the inexorable decline of the last twenty years and find sanctuary in the memory of Fergie’s revolution. I started to take a serious interest in football around 1975, aged six, when the club had won the sum total of two trophies in the previous nineteen years. Under Ferguson, in those late 1970s and early 1980s, they became a force unrecognisable to previous generations of their fans.

My father was never the type to keep a record of such things but he reckons he missed very few games at Pittodrie between 1948 and 1966, before he moved too far away to attend. He was a regular when they won the league in 1955, but for the most part he watched also-rans in red. The disappointments were endless. In 1953 he travelled to Glasgow and squeezed into Hampden as one of 129,000 who saw them draw with Rangers in the Scottish Cup final. True to form, they lost the replay. A year later he was back when they faced Celtic in front of 130,000. Same result: another defeat. In later years he endured the setbacks from the safety of his armchair.

Around the time I began writing this book Dad, now elderly, was hospitalised by an illness. After ten days he seemed comfortable and I was given the all-clear to fly to Luxembourg as one of the writers covering a Scotland friendly. There, on the media coach to the stadium, I received a call to say he had deteriorated rapidly over the previous few hours. Then a subsequent call: it might be advisable for the family to gather at the bedside. With their gentle euphemisms, the doctors hinted that he was unlikely to get through the night. The family duly gathered, but it was impossible for me to get back to him for another nine hours. Numbly, I sat in a little football ground, 800 miles away, quietly trying to compose a match report about a game that did not matter, asking players questions that did not matter, fearful that the phone would ring with the unwanted conclusion. You think of childhood at a time like that, of shared experiences, of laughter and celebrations. For me, those thoughts were inextricably bound up with Aberdeen under Alex Ferguson.

I made it back to Dad’s bedside. He made it through. Over the coming days he improved and a few weeks later was allowed home. A couple of years later, in March 2014, Aberdeen won the League Cup, their first trophy for nineteen years and only the fourth since Ferguson left. Dad watched it on television. His two wee grandsons were at the final among 43,000 Aberdeen supporters, a bigger following than even the unsurpassable 1980s teams drew. By the time my reports had been filed for the Herald that evening it was too late to call him. I knew he would be away early to his bed, but it was lovely to know how pleased he would be.

For almost four decades now any mention of ‘Fergie’ has brought the same reaction from him: a laugh, a shake of the head and a remark along the lines of ‘What a boy he is’. It is a response that makes me smile, too, because it affectionately paints Britain’s greatest manager as a likeable, irrepressible kid. Not a legend, not a genius. Not the red-faced septuagenarian whose place in history is now assured. Maybe just a young man with something to prove.

Only once, through all the barren years, do I remember Dad showing the strain of being a supporter of an underachieving club. It was the afternoon of the 1978 Scottish Cup final, Aberdeen’s last game before that ‘boy’ turned on the lights. I remember being puzzled that Dad’s seat was vacant and he was not at home to watch the game on television. A couple of hours later he meandered in after a session at the local. He was rarely a drinker, so why hit the bottle on a day with nothing to celebrate? ‘Drowning my sorrows, son,’ he said, smiling.

What happened at Hampden that day? Rangers 2, Aberdeen 1.

Now read on.

MICHAEL GRANT

May 2014

Chapter 1

‘CUP FINALS ARE TOO BIG FOR SOME PLAYERS’

Glasgow is a city that has always had its no-go areas; neighbourhoods even the streetwise would do well to avoid. In 1978 there was a case for saying Hampden Park was one of them. The famous old home of Scottish football was dirty and dilapidated, so neglected it had been reduced to an eyesore. ‘Hampden is dying,’ said the Scottish Football Association secretary Willie Allan in a mournful plea for external funding. The vast stadium’s exterior walls had become a canvas for graffiti about gang rivalries, or bigotry, or the English. Before big matches the area outside the turnstiles was littered with broken glass and muck from police horses. Inside, supporters had to endure an obstacle course of empty whisky and wine bottles, squashed beer cans, discarded ring pulls, carrier bags, food wrappers, cigarette ends and other human debris. Once the crowd was in, streams of urine would slowly snake down the terraces. Those enormous slopes were made out of cinder embankments. They were filthy.

There could be blood, too. The law still allowed fans to bring ‘carry-outs’ into the ground and segregation between opposing supporters was not strictly enforced. Drunkenness and Scottish football rivalries meant casual violence was inevitable. Heavy beer bottles would be thrown to smash down brutally on rival fans’ heads.

On cup final days the sweeping terraces would be filled with block after block of Rangers or Celtic supporters: 30,000, 40,000, maybe 50,000 of them, all noisy, cocksure, an elemental force not just confident of victory but insistent upon it. It felt as though any other team was only there to make up the numbers; to lose without a fuss and clear off home while the trophy was presented to one of its two rightful owners. In Glasgow, and especially at Hampden, day-trippers from Edinburgh, Dundee or Aberdeen were expected to know their place.

That was what awaited Aberdeen in the Scottish Cup final against Rangers on 6 May 1978. Whenever Rangers and Celtic played each other the two sets of fans would divide the ground evenly. When one of them faced any other club their fans would make up three-quarters of the crowd, and maybe more. It took strength of character to turn up in Glasgow knowing that your fans would be outnumbered to that extent. The Old Firm imposed their will on teams. Few who came to Hampden could cope.

Aberdeen were one of the perennial also-rans, outsiders who struggled to withstand Glasgow’s psychological onslaught. They had no real pedigree as winners and their only year as league champions had been nearly a quarter-of-a-century earlier. A few sporadic cup successes meant that by the 1970s their history was respectable, though Rangers and Celtic usually had the beating of them when it mattered. When Aberdeen routed Rangers 5–1 in the 1976–77 League Cup semi-final it was such a shock that even their own players struggled to comprehend what they had done. They stopped off at the studios of Scottish Television to watch the game again before getting back on the bus for the long drive home. They went on to beat Celtic in the final, too.

That triumph was sufficiently fresh in the memory to make the 1978 Scottish Cup final more interesting than usual. Their recent form had turned Aberdeen into the best team in Scotland. They began a 23-game unbeaten run in December 1977 and chased Rangers all the way to the last day of the league campaign. Between the start of the season and the cup final they had beaten Rangers and Celtic six times. Their impressive young manager, Billy McNeill, was tall and handsome. He was only thirty-eight, had been the iconic captain of Celtic’s Lisbon Lions, and came fresh from a decade of lording it over Rangers.

The match was a major event. Denis Law turned down an FA Cup final ticket so he could be in Glasgow to support Aberdeen, his home-town club. As one of the BBC’s commentary team he even got paid for being there. It felt like the whole North-East migrated to join him. British Rail scheduled five special trains

direct from Aberdeen to Hampden, and many more fans made the journey in a huge fleet of buses. The Daily Record’s front page headline read: FEVER PITCH–HAMPDEN RED ALERT AS BILLY’S ARMY ROLLS INTO TOWN. But this was an army rolling into Glasgow unprepared for the battle. As the Aberdeen support poured off the trains and buses, negotiated the broken glass and the shit from the police horses, and climbed the steps into Hampden, it suddenly hit them. Their first sight of the massed Rangers support, occupying vast swathes of the great open bowl, was overwhelming. Suddenly Aberdeen’s 20,000 seemed puny. Under the baking May sunshine they listened to the massed pipe bands and watched an Alsatian dog display team and a balloon competition on the pitch. And as kick-off approached, they grew nervous.

Yet, while they were outnumbered on the terraces and in the stands, their representatives on the pitch should be up for the fight. After all, Aberdeen had three men about to go to the World Cup finals in Argentina as part of Ally MacLeod’s Scotland squad: big, solid Bobby Clark in goal, tenacious Stuart Kennedy at right-back, the wee barrel of a goalscorer, ‘King’ Joey Harper, up front. And then there was the captain, the unflappable rock of their defence, Willie Miller. Those four were not the type to buckle. But something was not right. Aberdeen had not been in a Scottish Cup final for eight years and that seemed to prey on some of the players’ minds–and on the manager’s. On the eve of the game McNeill gave off strange signals to the papers. ‘There’s always tension for everyone involved,’ he told the writers. ‘But even being in the final is a marvellous thing for the city of Aberdeen.’ Some supporters felt uneasy. McNeill was a born winner but with that throwaway line he sounded content–perhaps resigned–simply to be taking part. No Old Firm manager would sound so passive.

There was more. ‘It’s a big day in their lives,’ said McNeill of his players. ‘Of course they will be nervous, but I’m sure they will get over that and settle down.’ Jock Wallace, Rangers’ grizzled, battle-hardened manager, took it all in. Their great wee winger, Davie Cooper, appeared in the papers on the morning of the game to give an entirely different message. He was photographed playing pool in his training gear as if he did not have a care in the world. There was no talk from Rangers about it being a big day in their lives, no mention of any of them being nervous. Cup finals were what Rangers did: 1978 was their ninth of the 1970s.

Fear

Fear Plague

Plague BZRK: Apocalypse

BZRK: Apocalypse Bzrk

Bzrk Love Sucks and Then You Die

Love Sucks and Then You Die Silver Stars

Silver Stars The Key

The Key Front Lines

Front Lines BZRK Origins

BZRK Origins Monster

Monster Gone

Gone The Snake

The Snake The Power

The Power Hunger

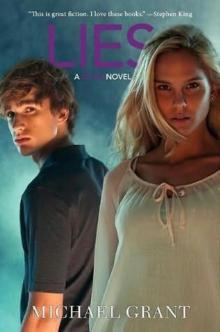

Hunger Lies

Lies A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Messenger of Fear

Messenger of Fear Eve & Adam

Eve & Adam The Trap

The Trap Light

Light An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam

An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam The Call

The Call Hero

Hero Soldier Girls in Action

Soldier Girls in Action Purple Hearts

Purple Hearts The Tattooed Heart

The Tattooed Heart The Fall of the Roman Empire

The Fall of the Roman Empire BZRK Reloaded

BZRK Reloaded Messenger of Fear Novella #1

Messenger of Fear Novella #1 The Magnificent 12

The Magnificent 12 Fear: A Gone Novel

Fear: A Gone Novel Villain

Villain Manhattan

Manhattan Eve and Adam

Eve and Adam Plague: A Gone Novel

Plague: A Gone Novel Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises In the Time of Famine

In the Time of Famine Hunger_A Gone Novel

Hunger_A Gone Novel Lies g-3

Lies g-3