- Home

- Michael Grant

Fergie Rises Page 2

Fergie Rises Read online

Page 2

Aberdeen fell to pieces at Hampden. They were jittery and hesitant, repeatedly giving the ball away and making the wrong decisions. For Rangers, the final became a stroll in their own backyard. Aberdeen no longer looked like a rising force, just another team of pretenders who could not handle the pressure. Rangers’ little midfield terrier Alex MacDonald ghosted between static defenders to force a header through Clark’s hands after thirty-five minutes. A thunderous, rumbling roar rose up from the Rangers end. Midway through the second half striker Derek Johnstone planted another header past the goalie. 2–0. Hampden throbbed again to Rangers’ support in full voice. Aberdeen pulled a goal back five minutes from time. But even that seemed pathetic. Left-back Steve Ritchie swung his leg at a low cross and scuffed the connection. The ball scooped high into the air and came down to hit the Rangers crossbar and post before going in as goalkeeper Peter McCloy swung on the bar with his back to the ball. The ball did not even touch the net. Aberdeen’s performance was so bad even their goal was embarrassing.

They had five minutes to find an equaliser, but were too beaten and broken to try. STV’s archives have only five minutes of highlights from the game, but that footage says it all. It shows Ritchie brushing off a couple of team-mates as they run up to celebrate; he is shaking his head, muttering gloomily to himself. For a team with momentum five minutes is long enough to score a second goal against suddenly nervous opponents. Aberdeen had no fight for that. No one in red even raced to grab the ball out of Rangers’ goal to force a quick restart. They were waiting to lose, waiting to get it all over with. Soon enough they were put out of their misery: Rangers 2, Aberdeen 1.

As the Rangers fans let rip, the Aberdeen end melted away, cursing another let-down. The familiar conclusions swirled around: same old Aberdeen, bottle merchants. Where were the leaders to stand up to Rangers and Celtic? Aberdeen had been men all season but under the pressure of Hampden they turned into mice. Later Joe Harper made it plain. ‘We simply froze and performed like a bunch of rabbits caught in the headlights. We were an embarrassment to all and sundry at Hampden.’ More than thirty years later the Aberdeen players who lined up that day still shake their heads at the memory. John McMaster, the elegant midfielder, knew they let people down. ‘It just caught up with us: the atmosphere, being anxious to do well in front of our families,’ he said. ‘The next thing it was, “What the fuck am I doing? I’m having a nightmare here”. All I did was frustrate myself. I chased Alex MacDonald all over Hampden. I didn’t play at all. A boy I’d grown up with said to me later, “John, you’re a legend, you’ve played in a Scottish Cup final.” I just thought, “How can you be a legend when you get beat?”’

Stuart Kennedy could not believe what he was seeing. ‘Cup finals are too big for some players. We’d beaten that Rangers team four times, beaten them 3–0 at Ibrox. But when you tell some people it’s a cup final I just don’t know what happens to them mentally. It’s like there’s more pressure on them. It didn’t bother me. I strolled through that game.’ McNeill had spoken softly to the players at half-time, assuming they would improve after an ‘awful’ first half. What they actually needed was a collective boot up the backside, and, too late, he realised it. The newspapers dismissed Aberdeen. ‘As one side was so far ahead of the other the 1978 Scottish Cup final will not be remembered as one of the classics,’ said the Glasgow Herald. ‘The Aberdeen heads went down and the shoulders slumped as Rangers turned it on as if taking part in an exhibition.’

By the time the team bus pulled away from Hampden and began the long retreat from Glasgow, the streets were thronged with jubilant Rangers fans, knocking back bottles and cans and pausing to jeer and flick V-signs at their vanquished foe. Miller scowled out of the window. The captain was quietly seething. He was a hard, born-and-bred Glaswegian who had grown into Aberdeen’s leader and icon. He knew the day had been a surrender from start to finish. ‘I swore that I would never allow a team that I was captaining to freeze on a big occasion,’ he said. But Miller could not change the entire club’s mentality on his own. Aberdeen needed someone to worm inside their heads, someone to tell them they were as good as the Old Firm. Better, even. They needed someone unafraid to get right into Rangers’ and Celtic’s faces. None of that came naturally to the earthy, reserved folk of the North-East.

Back home an open-top bus parade had been organised for the day after the cup final, win or lose. The players wondered if anyone would have that appetite for it, but it was a sunny holiday weekend and 10,000 made the effort to line the streets of Aberdeen’s city centre, and another 10,000 greeted them inside Pittodrie. They came to acknowledge the fine football their team had played in the five months before Hampden. Such was the dominance of the Old Firm that, as midfielder Gordon Strachan put it: ‘Even to appear in a Scottish Cup final was apparently cause for celebration.’ A HEROES’ WELCOME FOR GALLANT LOSERS, said the Glasgow Herald. It was not meant to sound like a backhanded compliment, but the fact remained that Aberdeen were losers. As they disembarked from the bus and walked out at Pittodrie the players looked glum. Their movements were slow and their shoulders drooped. Some held out their empty hands to the supporters in a gesture of apology.

McNeill tried to lift the mood with talk of what Aberdeen were building. Finishing second in the league and cup was only the beginning, he said. Next season they would bring home a trophy, he promised. The North-East had heard it all before. No one really believed anything would change: Rangers and Celtic would share the trophies again the following season, and again the season after that. Who was going to stop them?

A piece of lesser football news made one of the newspapers on the morning of the cup final. FERGIE STAYS ON, reported the Daily Record. ‘St Mirren manager Alex Ferguson is to stay at Love Street. Ferguson turned down an offer from the United States after meeting with the St Mirren board last night.’ It was an apparently insignificant story tucked away on one of the inside pages. Up in Aberdeen, one man read it and made a mental note.

Chapter 2

A DISCREET CALL TO THE JOLLY RODGER

Scotland fans had one thing on their minds going into the summer of 1978. After another long season there was little appetite for the ins, outs and intrigues of club management. There were now bigger fish to fry: Scotland were going to the World Cup finals in Argentina. Their effervescent, pied piper of a manager, Ally MacLeod, whipped the public into a state of collective hysteria. He was asked what he was going to do after the tournament? His answer: ‘Retain it.’

There was no ridicule of ‘Ally’ and his bombastic declarations. The country hung on his every word. When he decided it would be a good idea for supporters to come to Hampden and give the squad a send-off to the airport, more than 30,000 turned up to wave them away. MacLeod had mobilised a big football crowd, in a big football stadium, just to look at players standing on an open-top bus. Scottish comedian Andy Cameron captured the growing sense of expectation when he submerged himself in tartan and appeared on Top of the Pops to plough heroically through his World Cup novelty song ‘Ally’s Tartan Army’. Feverish excitement propelled the record to 360,000 sales and number six in the UK charts. Scotland had qualified for World Cups before, in 1954, 1958 and 1974, but they had never travelled with this sort of swaggering confidence. Fans were talking about Córdoba, Mendoza and the Pampas as if these places were to be invaded by a friendly but conquering army.

The newspapers’ ‘number one’ football writers–the main men–had already been despatched to Argentina when the tectonic plates moved back in Glasgow. Suddenly, the World Cup was knocked from the top of the football agenda. In the newsrooms and journalists’ watering holes the conversations revolved around two clubs, two men and two dramatic vacancies. It is a major story in Scotland when one of the Old Firm clubs changes their manager. For both of them to do so in the same week amounted to unprecedented turbulence. The sports desks of the Scottish national newspapers–all based in Glasgow, other than The Scotsman in Edinburgh–were in ferment. Now the

real stories were at home. First the back pages were dominated by the bombshell about Jock Wallace walking out on the Rangers job, without explanation, just days after that cup final defeat of Aberdeen secured the domestic treble. Wallace’s reasons remained vague and the sense of affront in the blue half of Glasgow hardly lessened when he took over modest Leicester City a few days later. Who would land the Rangers job? ‘St Mirren’s Alex Ferguson, the live-wire who has taken the Paisley club to success, became the favourite,’ wrote Hugh Taylor in Glasgow’s Evening Times. Taylor was wrong. Within hours of his paper hitting the streets Rangers had appointed from within. Their long-serving and distinguished captain, John Greig, was given the reins. Ferguson was never an option.

Jock Stein’s exit from Celtic after thirteen years as manager was less surprising or confusing, but more momentous given the slew of trophies he had brought the club, including the 1967 European Cup and nine consecutive Scottish titles. ‘Now comes the news which will rock the game in Scotland, down south, and indeed in any country where the game is played,’ declared the Evening Times. If this amounted to a footballing earthquake for Glasgow a secondary tremor was soon to hit Aberdeen. Twelve months earlier the Scottish Football Association had raided the manager’s office at Pittodrie, prised MacLeod out of Aberdeen and given him their top job. When the news about Stein broke, it was immediately obvious that Celtic would attempt the same with Billy McNeill. He was as ‘Celtic’ as anyone could get: the cornerstone of the Stein era, the first British captain to lift the European Cup, a colossal Parkhead figure. He was also emerging as a young manager with terrific prospects. It was Stein himself who first approached McNeill at an awards lunch in Glasgow and quietly offered him the position as his replacement.

McNeill had been with Aberdeen for less than a year. No one had to tell him he had a squad of outstanding potential, or that he might be on the brink of something special despite that cup final let-down. His players liked and respected him, the North-East had embraced him and McNeill and his wife enjoyed the city’s comfortable, relaxed way of life. The obvious and sensible thing to do was thank Celtic for their interest but reluctantly let them know the timing was not right. He felt grateful to Aberdeen, too, for giving him a platform in management by taking him away from Clyde and giving him a job with real profile. And yet, and yet…The thought nagged away at him that the chance to manage Celtic might never come his way again. Against his better judgment, he listened to heart rather than head and tendered his resignation.

In Paisley, Alex Ferguson had turned down that offer from the United States, but the story about him ‘staying on’ at St Mirren remained accurate for only twenty-four days. On 30 May the club’s exasperated board decided they had had enough of a manager they had come to see as confrontational and controlling, and unanimously decided to sack him for breach of contract. Ferguson was summoned to Love Street and a typed, numbered list of thirteen offences was read to him, before he was dismissed. A curt statement was issued: ‘Because of a serious rift which had occurred between the board and the manager, and because of breaches of contract on his part, it would be in the interests of both parties that the manager’s contract be terminated.’ The club’s supporters could not believe what they were hearing. Many thought Ferguson the best thing to happen to St Mirren in the nineteen years since their last major trophy in 1959. To most of Paisley the decision to sack him seemed as insane then as it has to the rest of football ever since. In essence, the issue was an irreparable personality clash with the chairman, Willie Todd. Ferguson visited his solicitors and insisted he would take St Mirren to an industrial tribunal for unfair dismissal. That decision would become a saga that drained his energy for months, distracting him as he tried to come to terms with his next job, the biggest of his managerial career to date.

The managers of Partick Thistle and Dumbarton, Bertie Auld and Davie Wilson, and the Southampton assistant Jim Clunie, were all linked with the Aberdeen vacancy when Billy McNeill departed. But not for long. It was quickly clear that Ferguson was the man Aberdeen wanted. They were impressed that under his tenures at East Stirlingshire and St Mirren not only had crowds leapt significantly, but he had built squads without troubling either board for money. Indeed, the exciting young team at Love Street was assembled for no transfer outlay and had quickly won promotion to the Premier League. Yes, the charismatic manager was clearly a handful for both sets of directors, but Ferguson’s results spoke for themselves. The more background checks done by Aberdeen chairman Dick Donald and vice-chairman Chris Anderson, the more convinced they were that Ferguson’s talent and potential outweighed any questions over impulsiveness or control issues. Anderson had been the interested reader of that snippet in the Record about Ferguson turning down the American offer on the day of the cup final. Donald and Anderson were confident in their judgment, having been so successful with MacLeod in 1975 and McNeill in 1977 that both managers were quickly poached for ‘bigger’ jobs.

Alex Ferguson and unemployment were never likely to suit one another. On leaving St Mirren he was out of work for a matter of hours. Given how quickly he would demonise ‘the Glasgow press’ for their hostility to Aberdeen it was ironic that the club first made contact with him through the quintessential Glasgow football writer, Jim ‘The Jolly’ Rodger. Rodger was in his mid-fifties and had been a prominent journalist for thirty years. He was a short, stout, bald, bespectacled man who enjoyed enormous influence and contacts. He was on first-name terms with Prime Ministers Harold Wilson and Margaret Thatcher; in football circles he routinely acted as a go-between in transfers and managerial appointments, effectively an agent in an age before agents. Ferguson had been similarly sounded out by Aberdeen about taking over when MacLeod left in the summer of 1977, but then he had turned them down; ‘Insanity,’ he admitted in a subsequent autobiography.

St Mirren have always disputed the timing of Rodger’s first contact with Ferguson. Their chairman, Willie Todd, later said that Ferguson had let it be known around St Mirren that he was moving to Aberdeen ‘four days before he eventually left’. If true, it would mean Ferguson had done so while McNeill was still deliberating over his move from Aberdeen to Celtic. Todd considered that a clear breach of contract because Aberdeen had made no formal approach to speak to him about the job. He claimed he sacked Ferguson because he could not tolerate a manager who was trying to work his ticket out of the club. It was always Todd’s view that Ferguson had been ‘tapped up’ by Aberdeen days, even weeks, before he actually went. But Aberdeen could not have known they were about to lose McNeill. They would have been unaware that Stein was about to leave Celtic. In fact, McNeill later admitted he had been embarrassed that the story broke on 26 May before he had spoken to the Aberdeen board. Whenever the call was made by Rodger, though, Ferguson told him he would jump at the Aberdeen job, and the journalist relayed that news to Donald. Ferguson and Donald then spoke by telephone and the following day the young manager travelled north for negotiations. These were concluded so swiftly that a press conference was called later the same evening.

‘I’m thrilled at joining Aberdeen because I want to win things,’ Ferguson told the reporters who rushed to Pittodrie. ‘You only need to look at the stadium and you can see it is ready for success.’ He looked relaxed and comfortable, answering all the questions before posing for pictures alone and with his new chairman. FERGIE HUSTLES NORTH TO BOSS THE DONS, said the headline on the front page of the Glasgow Herald the following morning. Journalist Ian Paul wrote that Aberdeen’s board ‘can be commended for the speed at which they moved’ in capturing ‘one of Scotland’s most exciting managerial prospects’. It was the end of a dizzying spell of activity. Wallace resigned on 23 May, Greig was appointed on 24 May, the Stein story broke on 26 May, McNeill resigned on 29 May, St Mirren’s board decided to sack Ferguson on 30 May, Celtic confirmed that Stein would become a director and appointed McNeill to replace him on 31 May, and Aberdeen appointed Ferguson on 1 June.

At last Scotland could take

a breath and focus its attention solely on the World Cup. Of course, the dream’s quick collapse felt apocalyptic: Scotland lost to Peru, drew with Iran and watched Archie Gemmill score a mesmerising goal in a futile win over Holland. Then the country turned viciously on MacLeod. Andy Cameron joked that there was a garage somewhere storing tens of thousands of copies of his record. He reckoned ‘Ally’s Tartan Army’ did not sell another copy from the day Scotland went out.

Chapter 3

RESCUING ALEX FERGUSON

Glaswegians have always laughed loudest at jokes about Aberdeen. Scotland’s population is concentrated in the central belt, especially around greater Glasgow, whose citizens tend to view the smaller north-eastern city as an inferior outpost. Many would struggle to place it on a map. Others think of Aberdeen as remote, rural, cold and dour. They imagine an all-pervading odour of fish. They call the locals ‘sheepshaggers’, and make wisecracks about a perceived meanness: ‘Copper wire was invented by two Aberdonians fighting over a penny’; ‘The first people in Scotland to get double glazing were Aberdonians so that the bairns couldn’t hear the ice cream vans’; ‘An Aberdonian found a pair of crutches so he went home and broke his son’s leg’.

So when Alex Ferguson moved to the north-east of Scotland, he stepped into a different culture and way of life. He was old enough to know Aberdeen as a popular holiday resort during Glasgow Fair, the July fortnight when Glaswegians traditionally took their summer break. Until the 1970s many had flocked to its guesthouses and its long, sandy beach. Then the sudden availability of cheap air travel to the Mediterranean broadened horizons and the traffic between the two cities dwindled. Not that Aberdeen had really enjoyed a picture postcard reputation. For decades its income had been based on agriculture, fishing, textiles and quarrying the famous granite–hence the nickname, ‘The Granite City’. The imposing stone made Aberdeen look steadfast and regal, but grey and unwelcoming, too. It also ensured stolidity. For decades the city’s population was static, its economy stagnant. During the 1960s it was little more than a regional backwater with no obvious prospect for growth, while 150 miles to the south Glasgow clung to its proud self-image as the second city of the British Empire and one of the world’s great hubs of heavy engineering.

Fear

Fear Plague

Plague BZRK: Apocalypse

BZRK: Apocalypse Bzrk

Bzrk Love Sucks and Then You Die

Love Sucks and Then You Die Silver Stars

Silver Stars The Key

The Key Front Lines

Front Lines BZRK Origins

BZRK Origins Monster

Monster Gone

Gone The Snake

The Snake The Power

The Power Hunger

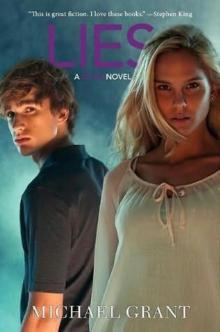

Hunger Lies

Lies A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Messenger of Fear

Messenger of Fear Eve & Adam

Eve & Adam The Trap

The Trap Light

Light An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam

An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam The Call

The Call Hero

Hero Soldier Girls in Action

Soldier Girls in Action Purple Hearts

Purple Hearts The Tattooed Heart

The Tattooed Heart The Fall of the Roman Empire

The Fall of the Roman Empire BZRK Reloaded

BZRK Reloaded Messenger of Fear Novella #1

Messenger of Fear Novella #1 The Magnificent 12

The Magnificent 12 Fear: A Gone Novel

Fear: A Gone Novel Villain

Villain Manhattan

Manhattan Eve and Adam

Eve and Adam Plague: A Gone Novel

Plague: A Gone Novel Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises In the Time of Famine

In the Time of Famine Hunger_A Gone Novel

Hunger_A Gone Novel Lies g-3

Lies g-3