- Home

- Michael Grant

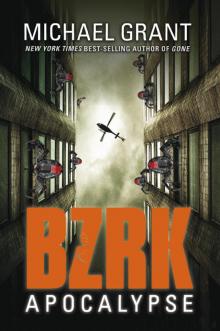

BZRK: Apocalypse Page 18

BZRK: Apocalypse Read online

Page 18

And then, he was out. Done by the afternoon. They’d promised him that.

Perhaps a nice piece of cod. He liked cod when it was not overdone.

Yes, the final chorus! Applause from the thousands, maybe tens of thousands of people in the square. Time to applaud, time to enlarge the benign smile, time to …

The Pope blinked.

Then he frowned.

What was that? What was he seeing? Some sort of … it looked like an insect, a bizarre insect. He was seeing it, but … but it was nowhere around him.

He looked around, puzzled and a little concerned. No one else seemed to see anything unusual.

And now … now another vision. Like a movie screen lit up inside his head, like two of them, really, and both of them showing fantastic insects.

The one insect, he could see its face.… He could … he was hallucinating. Clearly, he was hallucinating. Was it a stroke? He dreaded a stroke; his father had died at age fifty-four of a stroke.

The insect face … It …

“It’s me,” he said in his native Spanish.

Then, as quickly as it opened, one of the windows in his head closed. Gone.

“Ah!” he cried out. “Ah!”

He sank to his knees, and now everyone was looking at him, now the TV cameras and the phone cameras all swiveled toward him, as he cried, “Oh, oh, oh!”

The Pope began to laugh. He began to laugh and laugh and then he was screaming, he knew he was screaming, though he felt no pain.

He screamed and tore at his vestments.

The world was swirling colors, all zooming crazily around him, faces suddenly coming into focus, distorted, demonic faces.

Only when he grabbed an elderly woman’s walker and began attacking the children with it did anyone try to stop him.

In the end he was hauled away by Rome police and his own plainclothes Swiss Guards.

TWENTY-ONE

The sense of approaching doom was rising now. The country was scared. The world was scared. Glances were shielded. Heads were lowered. Shoulders hunched. Jaws tight. Voices too high or too low, too loud or whispering like a scared child.

Not as scared yet as it should be, no, not yet. But when people figured it out, the true panic would begin.

The Twins had pulled the trigger on massed preprogrammed attacks: Burnofsky had seen the footage of Stern. There would be more of that. Benjamin was in the driver’s seat increasingly, and Benjamin would have his apocalypse.

But that was nothing compared to what Lear was doing.

“Of course it’s Lear!” Burnofsky cried aloud, as though someone was arguing with him, as though he was fighting someone to make them understand.

Lear. What a clever, clever fellow he had turned out to be. Burnofsky saw it all now, saw the games, saw the ultimate destructive power that flowed from Grey McLure’s little lifesaving creatures.

Poor old Grey. They’d been friends, he and Burnofsky. The last friend Burnofsky had had. Poor old Grey, who had gotten his panties all in a twist when he learned Burnofsky was weaponizing nanobots for the Armstrongs. A lovely idealist, old Grey. A good man who just wanted to save his sick, dying wife.

Had he ever realized the destructive potential in his creatures? Had he even an inkling of what they could do in the wrong hands?

Fucking idealists. They were ever so useful to those with evil minds.

It was all coming down, Burnofsky thought. And when it did, the Twins were going to kill him. Kill him or rewire him.

That second thing made his stomach turn. He had endured it once, was still enduring it. But like many traumas, the threat of a repeat performance was even worse. He could not be used this way; he couldn’t be turned into some computer made of meat, rewrite, delete, up-arrow, down-arrow, parentheses, backslash.…

He had in some way accepted the first wiring as a sort of penance. He was a sinner, a terrible sinner, and he had deserved the punishment of having his mind crudely twisted this way and that. But not again. Not again. He had paid. Paid enough.

Not again.

Death? Death was nothing. Death was relief of pain.

That’s what he had told himself while sitting in his grim apartment with a gun in his mouth. He had lacked the courage to do it. But he would die before he would let them treat him like nothing. Like nothing.

“I paid,” he told the camera he knew was watching him. His lip curled into a vicious sneer. “I paid!”

His mind went inevitably to Carla, and the sickening result of that thought, the excitement, the pleasure of it. And with it the awful need to hurt himself.

He lit a cigarette. He watched the end burn a bright orange. The smoke curling, teasing the end of his nose, making his watery eyes water still more. Not tears, though. Not tears.

The Pope—that would push the Twins over the edge. They would have to realize that they were no longer the masterminds, just two more suckers playing Lear’s game. And then? Benjamin wouldn’t stand for it, oh, no. Lear would not take Benjamin’s Götterdämmerung from him. Benjamin would lose it, lash out, and at last unleash the gray goo.

He would use Burnofsky for that. Yes, of course. Burnofsky would serve the Twins one last time and destroy the world before Lear could do it.

It was funny, really—despite the way his eyes watered—it was funny, funny to think that in the end it would not be a race between destruction and salvation for humanity, but a race between two different lunatics, Benjamin and Lear, both bent on annihilation.

Well. Maybe not two.

Nanobots were his creation, not Benjamin’s. Poor old Grey had died in a fiery crash, lucky bastard, and his creations had become Lear’s. But Burnofsky still lived. Would go on living, probably, until the Twins decided they had squeezed the last from him.

“They’re mine,” he muttered, looking at a schematic of a nanobot. “I deserve a fucking prize. Hah! I deserve the fucking Nobel, hah!” Well, that was over, wasn’t it. Lear had sort of killed that whole thing, hadn’t he?

There was a bottle in the desk of one of his assistants. He had seen it, but he’d never said anything about it. It wasn’t his job to preach abstinence.

“It’s all coming down, anyway,” he muttered. “Twist me this way, twist me that way; in the end it’s all death.”

He watched the thoughts in his own mind, tracked them like the scientist he was. Not so easy, really, to predict the outcome of wiring, eh, Nijinsky? Poor dumb Bug Man had learned that when the president went off the rails. Not so easy.

Five minutes later the alcohol was raw in his throat and warm in his belly.

“I paid,” he said. And hurt himself again with a deep, deep swig.

“Hah!” Burnofsky said. “Fuck it. Fuck it all.”

His phone lay on the desk. He blinked at it. The icon for messages showed a three.

No one texted Burnofsky. In fact, he couldn’t recall the last time he’d had a text.

He almost didn’t look, but even carried off on a happy wave of blessed alcohol, he was still a servant to his own curiosity.

It’s Bug. Bad shit happening. Crazy bitch I think is Lear. Going to kill me and the whole damn world.

Then:

Are u there? Talk to me! I’m not playing.

Then:

Fuck! Do NOT call back. I’m using her phone. Can’t wait. I’ll try again later.

Burnofsky stared at the messages. His first thought: Anthony’s alive still? The Twins must be slipping.

And then, Jesus, he’s fallen in with Lear? And that made him laugh. Of course Anthony would end up back in some kind of world of shit. Of course he would.

And then he saw the words bitch and her.

Okay, he told himself, tamping down his excitement. Bitch could be slang for anyone, male or female. And the difference between he and her could be a simple mistyped letter.

Going to kill me and the whole damned world.

The Golden Hall in Stockholm. The Brazilians. That actress. The prince. The Pop

e. Even that slimy prick Nijinsky, of whose death he had at last learned.

“Yes, biot madness,” Burnofsky said. He gave himself a deep swig, feeling the savage joy of destruction, and the subtler pleasure of having his theory, his educated guess, ratified. He felt as if he was vibrating from the rush of discovery, the way he had when he used to make breakthroughs in the lab.

He could call the phone number back. Who would answer? Bug Man? Or Lear?

“Biot madness. Jesus Christ,” he said, voice an indecipherable slur. “BZRK. It’s a joke. It’s a goddamned joke.” Then, pushing himself back from his desk, shaking his head, he whispered, “Ah, no, not a joke: a game.”

With trembling fingers he hit the call-back button.

The number you have dialed is not a working number.

No, of course not. Lear would swap phones regularly, clever boy. Or girl. Could it really be a woman? Was a woman capable of such malice? Would a woman play this game?

He opened his browser. How did one get samples of DNA? Any hospital, sure, but these were samples from multiple countries. Who could do that?

He searched medical testing labs, impeded somewhat by the fact that he couldn’t quite direct his fingers to hit the right keys. He came up with too many results. He added qualifiers and came up with fewer hits. Then refined the search further to focus on corporate structures.

There were only six that were privately owned and reached beyond just North America. One of them, Janklow/MediStat, had recently lost its owner in an unfortunate boating accident.

“Accident. Hah.”

Among those present on the boat and giving statements to the police was another—competing—corporate titan. A woman.

Three seconds later he had a photograph looking at him from his monitor, the face of Lystra Ellen Alice Reid.

L. E. A. R.

He stared at the picture. He laughed. My God, a pretty young woman. That face, that serious, intelligent, attractive face hid a madness as profound as anything bubbling beneath the surface of two men so hideous they couldn’t walk down the street.

Lear. Self-aware madness, then. She knew, Lear did; the creator of BZRK knew she was mad. The wicked thing. The wicked, wicked thing.

He raised his mostly empty bottle to her in a wry toast. “Nice. Very nice.”

He could probably stop her. He could take this to the Twins, and they could probably stop her.

“I could save the world,” Burnofsky said, his tone mocking.

In the old days, he might have been tempted by that. He could be a hero. A hero/murderer. A hero who had helped to cause the suicide of the president of the United States. Right. Hero.

He could save the world.

Or.

Or he could beat Lear to the punch and shove it in the Twins’ face as well.

Hero? Sorry, Dr. Burnofsky, that role is no longer available to you. How about killer? How about destroyer of worlds?

Yeah, that position was still open.

“Why?” Keats asked it, though he knew it was foolish. How did you ask for explanations when the person you were asking might be wired himself? But he asked, anyway. “Why, Vincent?”

“I had my orders. From Lear. He gave me instructions.”

Plath licked her lips, nervous, angry, but feeling as if she should be far angrier. Knowing she should be far angrier. But somehow the emotion didn’t quite come. The rage did not rise in her. “Tell me what he instructed,” she said, her voice roughened to simulate the emotion she did not feel.

“He said to wire you. To reduce your skepticism. To avoid suspicion of Lear. Or of me.”

“What else?”

“Seventy percent,” Wilkes snarled. “Right.”

“There are … holes in my mind,” Vincent said. “I feel them. I know something is wrong with me. That’s not a lie.”

“Asshole!” Wilkes said, far more furious than Plath.

Plath raised a hand to silence Wilkes. “Tell me the rest,” she said to Vincent.

Anya sat beside Vincent, who seemed terribly small. She was weeping quietly, holding one of his hands in hers. Expecting him to be killed.

Plath saw herself through Anya’s eye. She saw a grim-faced girl, a sixteen-year-old girl with freckles for God’s sake, with stupid freckles. That picture of her finally brought the true emotion to the surface, but the emotion was disgust. Plath was disgusted with herself, with what she had become.

“Tell me what you did about the Tulip, Vincent,” Plath said.

Vincent flinched and broke eye contact. “You know what I did.”

“You wired the Tulip and the Twin Towers together,” Plath said bitterly. “And you looped in, what? Something that would make me less questioning, something …”

“I wired the memories of the Towers, the Tulip, and your pleasure centers, all together,” Vincent said. “They were Lear’s orders. That’s what he wanted. I …” He looked at Anya, and now Plath was looking at Vincent through her own eyes and through Anya’s. “I—”

“Did you at least argue? Did you at least question?” This was Keats now, raging. “Did you not say, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’ Did you not say, ‘How dare you?’ Did you not tell Lear to go fuck himself?” Keats looked as if he might beat Vincent to death right then and there.

“He’s been wired, too,” Plath said wearily. “We burned holes in his brain to save him, but someone else saw an opportunity in that. We never checked because … well, because we felt so sad and guilty. But Lear got to Vincent, Vincent got to me.”

“Who would have wired Vincent?” Keats asked, but even as the words were forming, he saw the answer. “Nijinsky. It’s like a disease. Lear to Nijinksy, Nijinsky to Vincent, Vincent to Plath. Like a virus.”

“Vincent, walk your biot out of me,” Plath ordered. “Do it now.”

Vincent said nothing, just looked at her, so Wilkes dropped down beside him, clapped a friendly hand on his leg, and in a flash there was a knife in her free hand. She jabbed the point against his carotid artery. “Do what the lady says, Vincent. Or I have to kill you. Give up the one you have in her, and your others, too. It’s either that or you die.”

“Do it, Vincent,” Anya pleaded. “For me, do it.”

Half an hour later Vincent’s biots were in a vial hanging from Plath’s neck. Vincent, the once-invincible Vincent, was still just seventy percent. But he was one hundred percent in Plath’s power.

STATE OF PLAY

Enough dots had been connected. But twenty-four hours after the day of the prince and the Pope, no one had an explanation. The prince was locked in a comfortable room in the palace and tranquilized to near coma.

His Holiness was locked in comfortable rooms at the Vatican, tied to his bed, and tranquilized to near coma.

Stockholm was fresh out of psychiatric beds in its institutions.

And then the new head of Wells Fargo bank drove her car off a bridge.

And several hours after that the Ayatollah Aliabadi was discovered amid broken glass cutting his wrists.

And the fashion model who leapt out of a tenth-floor window in Kyoto.

And the rock star who stormed offstage at a concert in Toronto, only to return a few minutes later, armed with a pistol, which he emptied into the audience, killing one and injuring four.

And the president of the World Bank who swam frantically into the Baltic Sea in freezing conditions. He was rescued but had to be confined.

It soon became hard to keep track of.

The Christmas Crazy, it was called, though it had begun earlier. The Season of Hope, as some faiths called it, had taken a very grim turn.

The world was on edge. The world was baffled and frightened but still somewhat amused, as it was only prominent people being affected by whatever bizarre syndrome was occurring.

But then a tenth-grade teacher in Larkspur, California, began attacking students with a knife. Five injured, one critically.

And a soldier at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, grabbed h

is AR-15 and began shooting up the officer’s club. Seven dead, three critically wounded.

The word was out: listen for people who claim to suddenly be seeing things in their head. Especially if they claim to be seeing strange insects.

Grab them, restrain them immediately, or at least get the hell out of the vicinity.

All over the world events were being postponed or canceled. All over the world people eyed each other with suspicion bordering on paranoia.

Then … nothing. For twenty-four hours.

Some dared to hope that it—whatever it was—was over.

Others wondered if whoever was behind this—aliens were the top choice—was just taking a break in order to build up to something even more unsettling.

The Centers for Disease Control and counterparts all over the world were in panic mode, searching for the cause, or at least the common thread. But it was a business consultant, who worked frequently with major medical clients, who made the tentative connection on his blog.

This person, David Schiller, sixty-three, suggested that, based on limited available data, it seemed those affected were more likely than the norm to have had lab work done. Medical tests. Blood tests. Urine samples.

He wrote this up on his blog. The dozen or so readers who saw the post wrote in comments that they would be very interested to see this developed further.

Sadly Schiller was unable to post a follow-up, as six hours after he published his blog post he was arrested by Chicago police for barbecuing one of his beloved Samoyeds on a fire he built in his front yard.

His blog was hacked and deleted.

The world was frightened. On edge. Desperate for some peace or some explanation.

The world was ready.

And so was Lear.

TWENTY-TWO

“I don’t know how I feel,” Plath said. “I feel …”

“It’s probably weird,” Keats said.

“Hollow.”

They had walked out of the safe house, both feeling that there was too little air in the place, both needing to be reassured that the outside world still existed.

Fear

Fear Plague

Plague BZRK: Apocalypse

BZRK: Apocalypse Bzrk

Bzrk Love Sucks and Then You Die

Love Sucks and Then You Die Silver Stars

Silver Stars The Key

The Key Front Lines

Front Lines BZRK Origins

BZRK Origins Monster

Monster Gone

Gone The Snake

The Snake The Power

The Power Hunger

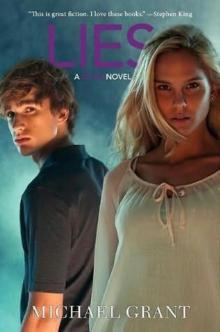

Hunger Lies

Lies A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Messenger of Fear

Messenger of Fear Eve & Adam

Eve & Adam The Trap

The Trap Light

Light An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam

An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam The Call

The Call Hero

Hero Soldier Girls in Action

Soldier Girls in Action Purple Hearts

Purple Hearts The Tattooed Heart

The Tattooed Heart The Fall of the Roman Empire

The Fall of the Roman Empire BZRK Reloaded

BZRK Reloaded Messenger of Fear Novella #1

Messenger of Fear Novella #1 The Magnificent 12

The Magnificent 12 Fear: A Gone Novel

Fear: A Gone Novel Villain

Villain Manhattan

Manhattan Eve and Adam

Eve and Adam Plague: A Gone Novel

Plague: A Gone Novel Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises In the Time of Famine

In the Time of Famine Hunger_A Gone Novel

Hunger_A Gone Novel Lies g-3

Lies g-3