- Home

- Michael Grant

Monster Page 2

Monster Read online

Page 2

Up and over her mother’s face.

CHAPTER 1

The Meet Cute

“THE FIRST SUPERHERO was not Superman,” Malik Tenerife said to Shade Darby. “It was Gilgamesh. Like, four thousand years ago. Superstrong, supersmart, unstoppable in battle.” He raised a finger for each point.

“First name Gil, last name Gamesh?”

“That’s very cute, Shade. Pretty sure they were making that same joke four thousand years ago. Gilgamesh, baby: the first superhero.”

“Not going with Jehovah?”

“I don’t think gods count as superheroes,” Malik said.

“Mmmm. They do if they aren’t real gods,” Shade countered. “I mean, Wonder Woman is an Amazon, Thor is one of the gods of Asgard, and wasn’t Storm from X-Men some sort of African deity?”

Malik sat back, shaking his head. “You know, I kinda hate when you do that.”

“Do what?” Her innocent expression was not convincing, and she didn’t really intend it to be.

“When you pretend not to know something and then kneecap me.” For a boy who supposedly hated it, he was smiling pretty broadly.

Shade laughed delightedly, something she rarely did. “But it’s so fun.”

His face grew serious and he leaned forward across the tiny table. “Are you really going to do this, Shade? You know it’s a felony, right? A federal crime? Worse, this is national security we’re talking about.”

Shade shrugged. They were at the Starbucks on Dempster Avenue, in Evanston, Illinois. It was busy, jammed with the usual early morning crowd—college kids, ponytail moms, two women in the fluorescent vests of road workers, high school kids like Shade, college kids like Malik, all breathing steam and tracking wet in on their shoes, all stoking the caffeine furnace.

It was noisy enough that they could talk without too much concern for being overheard, but Shade wished Malik had not used the word “felony,” because that was exactly the kind of word people had a tendency to overhear.

They sipped their drinks—Grande Latte for Malik, Tall Americano with a little half-and-half for Shade—checked the time, and left. Malik was a tall, lithe black boy, seventeen, with hair in loose ringlets that had a tendency to fall into his eyes, the endearing effect of which he was quite well aware. Those occasionally ringleted eyes were perpetually at half-mast as if to conceal the penetrating intelligence behind them. His expression at rest was benign skepticism, as if he was not likely to believe you but would keep an open mind.

Shade was a seventeen-year-old white girl with auburn hair cut to give her the look of someone who might be inclined to curse, smoke weed, and just generally be trouble. Only two of those things were true.

She had brown eyes that could range from amused and affectionate to chilly and unsettling—effects she deployed quite consciously. She was tall, five foot eight, and had the sort of bone structure that would have caused people to say, “Hey, you should be a model,” but for the impressive scar that ran just beneath her jaw on the right side and behind her ear and gave her a swashbuckling air. If there were ever a movie role for Blackbeard’s pirate niece, Shade would have been a natural for the part.

Shade was effortlessly charismatic, with a hint of something regal about her. But despite the charm and the cheekbones, Shade was not a popular kid at school. She was too bookish, too aware, too impatient, too ready to let people know she was smarter than they were. And beyond that, there was something about Shade that felt too old, too serious, too dark; maybe even something a bit dangerous.

Malik knew where that feeling of danger came from: Shade was obsessed. She was like some online game addict, but her obsession was with a very real event, with fear and death and guilt. And it was no game.

It was chilly out on the street, not real Chicago cold—that was coming—just chilly enough to turn exhalations to steam and make noses run. The little business section of Dempster—Starbucks, pizza restaurant, optometrist, seafood market, and the venerable Blind Faith Café—was just west of the corner at Hinman Avenue. Hinman—where Shade lived—was a street of well-tended Victorian homes behind deep, unfenced front lawns. Trees—mature elms and oaks—had already dropped many of their leaves, gold with green accents, on lawns, sidewalks, the street, and on parked cars, plastering windshields with nature’s art.

Shade and Malik walked together down to Hinman where the bus stop was. There were six kids already milling around.

“Well, I’ll see you, Shade,” Malik said. There was something off in the way he said it, a tension, a worry.

Shade heard that note and said, “Stop worrying about me, Malik. I can take care of myself.”

He laughed. He had an unusual laugh that sounded like the noise a hungry seal made. Shade had always liked that about him: the idiot laugh from such a smart person. Also, the smile.

And also the feel of his arms and his chest and his lips and . . . But that was all past tense now. That was all over and done with, though the friendship remained.

“It probably won’t work,” Malik said.

“Are you rooting against me?” Shade asked archly.

“Never.” The smile. And a sort of salute, fist over heart, like something he’d probably seen on Game of Thrones. But it worked. Whatever Malik did, it generally somehow worked.

“I’m going to do it, Malik. I have to.”

Malik sighed. “Yeah, Shade, I know. It’s called obsession.”

“I thought that was the name of a perfume,” she joked, not expecting a laugh and getting only a very serious look from Malik.

“You know you can always call me, right?”

Shade lifted her cup to tap his and they had a cardboard toast. “You should not be hitting on high school girls,” she said.

“What choice do I have? Northwestern girls aren’t dumb enough to buy my line of bullshit,” he said, and started to go, walking backward away from her, toward the Northwestern campus just a few blocks north. “Anyway, you’ll be a college girl next year.”

He was six months older than her, always a year ahead.

“Also, wasn’t the Sandman basically a god . . . ,” Shade called after him.

“I’m going to class now,” Malik said, and covered his ears. “I can’t hear you. Lalalalala.”

But Shade’s focus had already shifted to the new kid at the bus stop. A Latino boy, she guessed. Tall, six-two, quite a good-looking kid.

Wait. Nope. Maybe not a boy, exactly.

Interesting.

He or possibly she looked nervous, the new kid. His dark eyes were wary and alert. And made up, with just a little eyebrow pencil and a delicate touch of mascara.

The others at the stop were a pair of freshmen boys who looked like they should still be in middle school; a black kid named Charles or Chuck or something—she couldn’t recall—who had never yet been seen without earbuds; and two massive, muscular members of the football team, one white, one black, neither in possession of a definable neck.

“That is going to be trouble,” Shade muttered under her breath. Both of the Muscle Twins were eyeballing the new kid with a bored, predatory air.

No one spoke to Shade as she positioned herself a little apart, on the sidewalk, where she could watch. She sipped her coffee and waited, watching the football guys, noting the nudges and the winks. She could smell violence in the air, a whiff of testosterone, sweat, and pure animal aggression.

She noticed as well that the new kid was quite aware of potential trouble. His eyes darted to the football players, and when they moved behind him, Shade could practically see the hairs on the back of his neck stand up.

Evanston had always been the very epitome of enlightened tolerance, but a perhaps gay, perhaps trans kid and bored football players with their systems pumped full of steroids did not always make for a good mix. And lately Evanston had begun to change, to fray somehow, to fade a little as if it were a movie being shown on a projector with a dimming bulb.

“Hey, answer a question for us,�

�� the white player said to the new kid. Shade saw the newbie flinch, saw him withdraw fractionally, but then, with a will, recover his position and face up to the player who was an inch shorter but heavier by probably a hundred pounds of muscle.

“Okay.” It was a distinctly feminine voice. Shade cocked her head and listened.

“What are you?”

There was a split second when the new kid thought about evading. There was even a quick glance to plan an escape route. But he didn’t back down.

“My name is Cruz,” the kid said. He wore his black hair long and loose, almost to his shoulders, swept to one side. Shade shook her head imperceptibly, watching, analyzing.

“Didn’t ask your name, asked what you are.” This from the black player. “See, I heard you’re crazy. I heard you think you’re a girl.”

Shade nodded. Ah, so that was it. Shade was gratified to have an answer. She had never really talked to a trans person before, maybe she should make an effort to meet this new kid—assuming he survived the next few minutes.

Mental check: he or she? Shade made a note to ask Cruz which worked best for him. Or her. And decided in the meantime to insert female pronouns into her own internal monologue. Not that her internal monologue—or her pronoun choices—would matter to the kid who, from all indications, was seconds away from serious trouble.

Cruz licked her lips, glanced up the street, and sighed in obvious relief: the school bus was wheezing and rattling its way up the street. Thirty seconds, Shade figured. Cruz thought she was safe, but Shade was not so sure.

“I don’t think I’m a girl, and I don’t think I’m a boy, I just am what I am,” Cruz said. There was some defiance there. Some courage. Cruz wasn’t small or weak, but she was both when compared to the football players.

“You either got a dick or you don’t got a dick.” The white one again. Obviously a philosopher. Shade had the vague sense that his name might be Gary. Gary? Greg? Something with a “G.”

“You seem way too interested in what I have in my pants,” Cruz said.

Shade winced. “Mmmm, and there we go,” she said under her breath.

The bus rolled up, wheels sheeting standing water from the gutter. It was the black one (who Shade believed was named Griffin . . . or was she confusing her “G” names?) who shoved Cruz into the side of the still-moving bus.

Cruz lost her footing, staggered forward, and threw up her hands too late to entirely soften the impact of her face on yellow-painted aluminum. There was a definite thump of flesh-padded bone against aluminum, and the rolling bus spun Cruz violently, twisted her legs out from under her, and she fell to her knees in the gutter.

The bus stopped, the door opened, and the gnome of a driver, oblivious, said, “Let’s move it, people.”

Earbud boy and the two frightened freshmen, as well as the two lumbering thugs, all piled aboard.

“There’s a kid hurt out here,” Shade told the driver.

“Well, tell him to get on board, he can see the nurse when we get to school.”

“I don’t think she can do that,” Shade said.

Cruz sat on the curb. Blood poured from her nose, and hot tears cut channels in the red, all in all a rather gruesome sight.

Don’t think about a face covered in blood. Don’t go back to that place.

Shade made a quick decision, an instinctive decision. “Go ahead, I’m taking a sick day,” Shade told the driver. The bus pulled away, trailing vapor and fumes.

“Hey,” Shade said. “Kid. You need me to call 911?”

Cruz shook her head. Her breath came in gasps that threatened to become sobs.

“Come with me, I’ll get you a Band-Aid.”

Cruz stood and made it most of the way up before yelping in pain as she tried her left ankle. “Go ahead, I’ll be fine,” Cruz said. “Not my first beating.”

Shade made a soundless laugh. “Yeah, you look fine. Come on. Throw an arm over my shoulders, I’m stronger than I look.” For the first time the two of them made eye contact, Cruz’s tear-filled, furious, hurt, expressive brown eyes and Shade’s more curious look. “I live just down the block. You can’t walk and you’ve got blood all down your face. So either let me call 911, or come with me.”

It was all said in a friendly, easygoing tone of voice, but much of what Shade said tended to have a command in it, like she was talking to a child, or a dog. Lack of self-confidence had never been an issue for her.

They nearly tripped and fell a few times—Cruz had to lean heavily on Shade—but in the end they made their way down the sidewalk and turned left onto the walkway that led through a gate, beneath the tendrils of an overgrown and fading panicle hydrangea bush, to Shade’s back door.

They entered through a kitchen much like every other kitchen in this well-heeled neighborhood: granite counters, a restaurant-quality six-burner stove, and the inevitable double-wide Sub-Zero refrigerator. Shade fetched a baggie, filled it with ice, and handed it to Cruz.

“Come on.” They headed upstairs, Cruz holding the carved-wood railing and hopping, with Shade behind her ready to catch her if she fell backward.

Shade’s room was on the second floor, walls a cheerful yellow, a gray marble bathroom visible through a narrow door. There was a queen-size bed topped by a white comforter. A desk was against one wall. A dormer window framed a padded window seat.

And there were books. Books in neat shelves on both sides of the desk, between the dormer and the southwest corner, piled around the window seat, piled on an easy chair, piled on Shade’s bedside table.

Shade swept a pile of books from the easy chair and Cruz sat. Shade stepped into her bathroom and came back with a bottle of rubbing alcohol, tissues, a yellow tube of Neosporin, a box of bandages, and a glass of water.

“Put your leg up on the corner of the bed,” Shade instructed. Cruz complied and Shade laid the ice bag over the twisted ankle. “Take these. Ibuprofen; it will hold the swelling down and dull the pain.”

“You’re being too nice,” Cruz said. “You don’t even know me.”

“Mmmm, yes, that’s what everyone says about me,” Shade said with a droll, self-aware smile. “That I’m just too darn nice.”

Cruz carefully wiped blood away, using her phone as a mirror. Then, suddenly remembering, she pulled a small, purple Moleskine notebook from her back pocket. It was swollen from curb water in one corner, but otherwise unharmed. Cruz stuck it into a dry jacket pocket with a sigh of relief as Shade fetched a trash can for the bloody Kleenex.

“Shade Darby, by the way. That’s my name.”

“Cool name.”

“It’s something to do with the moment of my conception. I gather there were trees. Not the kind of thing I ask too many questions about, if you know what I mean. And you’re Cruz.”

Cruz nodded. “In case you’re wondering, I have a dick.”

That earned a sudden, single bark of laughter from Shade, which in turn raised a disturbing red-and-white smile from Cruz.

“Is that a permanent condition?” Shade asked.

Cruz shrugged. “I don’t have a short answer.”

“Give me the long one. I’ll tell you if I get bored.” She flopped onto her bed.

“Okay. Well . . . you know it’s all on a spectrum, right? I mean, there are people—most people—who are born either M or F and are perfectly fine with that. And some people are born with one body but a completely different mind, you know? They know from, like, toddler age that they are in the wrong body. Me, I’m . . . more kind of neither. Or both. Or something.”

“You’re e), all of the above. You’re multiple choice, but on a true-false test.”

That earned another blood-smeared grin from Cruz. “Can I use that line?”

“I understand spectra, and I even get that sexuality and gender are different things,” Shade said, sitting up. “This is not Alabama, after all. Or it didn’t used to be. Our sex ed does not end with Adam and Eve.”

“You’re . . . unusual,” Cr

uz said.

“Mmmm,” Shade said.

“I like boys, mostly,” Cruz said with a shrug. “If that clears anything up.”

“Me too,” Shade said. Then, with a small skeptical sound, she added, “In theory. Not always in reality.”

Cruz gave her a sidelong glance. “I saw you with that boy, the tall, dark, and crazy-good-looking one?”

“Malik?” Shade was momentarily thrown off stride. She was not used to people as observant as herself.

“He likes you.”

“Liked, past tense. We’re just friends now.”

Cruz shook her head slowly, side to side. “He looked back at you, like, three times.”

“So, you’re a straight girl trapped in the body of a gay boy? Walk me through it.” Shade deliberately shifted the conversation back to Cruz, and she was amused and gratified to see that Cruz knew exactly what she was doing.

Smart, Shade thought. Too smart? Just smart enough?

“I am e), all of the above, trapped in a true-false quiz,” Cruz said. “You can quote me on that.”

“Pronouns?”

Cruz shrugged. “More ‘she’ than ‘he.’ I don’t get bitchy about it, but, you know, if you can . . .” Now it was Cruz’s turn to shift the topic. “You read a lot.”

“Yes, but I only do it to make myself popular.” The line was delivered flat, and Shade could see that Cruz was momentarily at a loss, not sure if this was the truth, before realizing it was just a wry joke.

It took Cruz maybe a second, a second and a half, to process, Shade noted. Slower than Shade would have been, slower than Malik, but not stupid slow, not at all. Just not genius quick.

“I’ll call us in sick,” Shade said, and pressed her thumb to her phone.

“I don’t think you can do that.”

“Please.” Shade dialed, waited, said, “Hello, this is Shade Darby, senior. I’m feeling a little off today, and I’m also calling in sick for—” She covered the phone and asked, “What’s your legal name?”

Fear

Fear Plague

Plague BZRK: Apocalypse

BZRK: Apocalypse Bzrk

Bzrk Love Sucks and Then You Die

Love Sucks and Then You Die Silver Stars

Silver Stars The Key

The Key Front Lines

Front Lines BZRK Origins

BZRK Origins Monster

Monster Gone

Gone The Snake

The Snake The Power

The Power Hunger

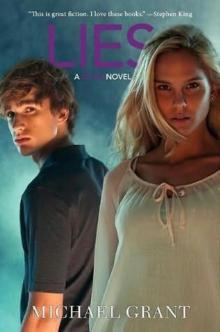

Hunger Lies

Lies A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Messenger of Fear

Messenger of Fear Eve & Adam

Eve & Adam The Trap

The Trap Light

Light An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam

An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam The Call

The Call Hero

Hero Soldier Girls in Action

Soldier Girls in Action Purple Hearts

Purple Hearts The Tattooed Heart

The Tattooed Heart The Fall of the Roman Empire

The Fall of the Roman Empire BZRK Reloaded

BZRK Reloaded Messenger of Fear Novella #1

Messenger of Fear Novella #1 The Magnificent 12

The Magnificent 12 Fear: A Gone Novel

Fear: A Gone Novel Villain

Villain Manhattan

Manhattan Eve and Adam

Eve and Adam Plague: A Gone Novel

Plague: A Gone Novel Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises In the Time of Famine

In the Time of Famine Hunger_A Gone Novel

Hunger_A Gone Novel Lies g-3

Lies g-3