- Home

- Michael Grant

In the Time of Famine Page 2

In the Time of Famine Read online

Page 2

“Michael, you look so sad.”

Moira, suddenly standing in front of him, took his hands and pulled him to his feet. Michael cursed himself. All night he’d been carefully avoiding her, but distracted by his thoughts, he hadn’t seen her approach. By the way she was swaying he knew she’d had too much to drink.

“Michael…” Her eyes glistened and she threw her arms around him.

He pushed her away gently. “Moira, tis a lovely weddin’. I hope you and Bobby will be very happy.”

“We will.” She wiped her eyes with a sleeve. “We could of had a good life together, you and me, if—”

“You’re Bobby’s wife now. Don’t be talkin’ like that.”

She sniffled. “You’re right, Michael, and I’m gonna make him a good wife. At least he appreciates me.”

“As well he should.” Michael lowered his voice. “Moira, what happened between you and me is no one else’s business. Isn’t that right?”

“Aye.”

To make sure he was getting through to her, he added, “It would go bad for both of us if anyone found out.”

“Aye, it would.” Even through a poteen fog she recognized the truth in that statement.

“There’s a good girl.” He gently pulled his hands from hers. “Now go and find your new husband.”

“I will.” She leaned close to him and for a moment he thought she was going to kiss him, but instead she whispered, “You’re a no good bastard, Michael Ranahan.”

“I am. Indeed, I am.”

She nodded solemnly and moved off unsteadily.

To shake his melancholy, Michael took a couple of turns around the bonfire with several girls, but his heart wasn’t in it. Just as he made up his mind to go home, he saw Bobby Ryan heading toward him and the big man didn’t look at all happy. Ah, Jasus, Michael thought. She’s gone and blabbed her mouth and now I’m in for it.

Bobby Ryan was two inches taller than Michael and at least fifty pounds heavier. Michael had always appreciated the man’s physical size when they’d been on the same side in a fight. But he didn’t feel that way now as he watched the big man lumbering toward him, unsteady on his feet. Bobby had tears in his eyes. Was it something his wife told him or was it the poteen? Michael couldn’t tell. He sighed in resignation and braced himself for the fight that was sure to come.

Bobby stepped up to Michael, his barrel chest heaving with emotion. He looked down at Michael for a moment and then threw his arms around him. “Me old friend,” he squeezed Michael in a crushing bear hug. “Thanks for everythin’.”

“I didn’t do anythin’,” Michael said, his voice muffled in Bobby’s chest.

Bobby let Michael go and slapped two beefy hands on Michael’s shoulders so hard it made him wince. “I know you and Moira… well, no matter”—he wiped a tear from his eye with his sleeve—“I’m a very happy man this day.”

“So am I, Bobby.” Michael exhaled in relief. “You have no idea.”

After the drunken groom lumbered off, Michael tried to slip away, but each time he kept getting pulled back to dance by one of the girls.

He was taking a breather on the sidelines, talking to Doyle and Scanlon, when Fowler danced by holding Moira very tightly. Michael glanced around looking for Bobby, wondering why he would let his brand new wife dance with the likes of Jerry Fowler. Then he saw Bobby curled up under a tree sound asleep.

It’s none of my business, he told himself. Then Fowler and Moira danced by again and Moira looked at him with pleading eyes and he realized that Fowler wouldn’t let her go.

Michael grabbed Fowler’s arm and pulled him away. “All right, Jerry. I think Moira’s had enough dancin’ for tonight.”

Fowler’s eyes gleamed brightly in the firelight. “Ah, is it your turn then?”

“Go home and sleep it off, Fowler. You never could hold your jar.”

As Michael turned away, Fowler took a swing at him and caught him on the side of the head. Michael ducked and drove his fist into Fowler’s exposed belly. As Fowler doubled over, Michael came down on the back of his neck with both hands. Fowler dropped to the ground.

Suddenly Pat Doyle’s huge arms were around Michael’s chest and he was thrown to the side like a sack of flour. “That’s enough the two of yez.”

He dragged Fowler to his feet. “Jerry, it’s time for you to go home now. There’s a good lad.”

Even in his drunken state, Fowler knew better than to challenge the big man. He shot a cold grin at Michael and stumbled off into the darkness.

“Thanks,” Moira said to Michael.

“Why don’t you wake your husband and go on home,” Michael said.

“Aye, I think that’s a good idea.”

Chapter Three

When the sun came up—it was the first time Michael had seen a rising sun in weeks—only he, of all the revelers, was awake to witness it. Enjoying the solitude of the moment, he watched the sun paint the peaks of the eastern mountains a golden hue as the birds took to the air in search of a meal. The fire had long since burned to embers and the dancers slept where they’d fallen. Old Genie, his back propped up against a tree, hugged his fiddle and snored softly. The morning air was chilly and wisps of morning fog swirled among the trees. Michael moved among the tangle of sleeping dancers until he found his brother with his head resting in Maureen’s lap. He nudged him with the tip of his brogue. “Come on little brother, time to go to work.”

Dermot opened one blood-shot eye and ran his tongue over his parched lips. “It was a good weddin’, Michael. Countin’ yours, there was only three fights the whole entire night.”

It had been a good wedding, but now it was time to pay the piper and it was a brutally long day mowing wheat with a poteen hangover. Dermot, even more irritable than usual, cursed the wheat, the scythe, the land, and his life in general.

In contrast, Michael was in high spirits. He didn’t know he’d been whistling until Dermot croaked, “For the love of God will you stop that infernal noise?” The reason for Michael’s euphoria was that while he’d sat watching the sun come up, he’d finally made up his mind.

He was going to America, by God, and that was that.

Dermot straightened up. “Jasus, me head’s killin’ me. Let’s take a blow.”

Dermot flung the scythe to the ground and flopped down on a pile of mown wheat. He rolled over on his back and held his head with his hands. “God, I’m fecken dyin’.”

Michael leaned on his scythe and surveyed the field. “We’ll be done by sunset.”

“And we’ll be back tomorrow to bundle it up. It’s destroyin’ me I tell ya.”

Michael had long ago learned to ignore his younger brother’s chronic complaining. As Dermot droned on, Michael’s attention focused on a flock of sheep in the distance—small white dots, slowly moving across a mottled green hill. Then his gaze shifted to the light and dark patterns the wheat bundles made in the next field. In the field beyond, two cows slowly clomped down the hill toward a flowing stream. It suddenly occurred to him what he was doing. He was looking at—things. It was as though he were trying to commit to memory the land that he would soon leave forever.

Forever.

Such a forbidding word. It was a word he’d never used about himself before. Death was forever. Burning in hell was forever. But the simple truth was, when he left this land, he would be going away—forever.

His eyes swept the landscape with its infinite shades of green. It truly was a beautiful land. The land that he was born on. The land that his Da was born on, and his Da before him. Michael felt a tightening in his throat. He would miss it.

Forever.

He looked over his shoulder and saw a wagon coming across the field.

“Da’s comin’.”

Dermot sprung to his feet too quickly and clutched his head. “Oh, Jasus…”

As Da reined in the wagon, Dermot swung the scythe too low and the blade struck a rock with a loud metallic twang.

Jasus, Mary an

d Joseph!” Da jumped down from the cart, snatched the scythe from Dermot, and examined the blade. “If you break it, how am I to pay for another?”

Dermot shrugged.

Da felt the anger rising in him. What was it about Dermot that just a mere shrug could make his blood boil? He was about to say something to him, but changed his mind. Instead, he turned to his eldest son. “Come on, we’ve supplies to pick up.”

“Why can’t I go?” Dermot protested. “You always take him.”

Michael wiped his forehead with his sleeve. “Take him, Da. I’ll finish up here.”

“I’ll do no such thing. He’ll disappear and I’ll have to do all the work meself.” He shoved the scythe into Dermot’s hands. “When I get back I want to see three more courses done. And mind you leave something for the Pooka.”

Michael turned away so his father wouldn’t see him grin. Unlike his superstitious father, Michael did not believe in fairies and hobgoblins. Da, on the other hand, was firmly convinced that the Pooka, which was said to be a small, deformed goblin, demanded a share of every crop at the end of the harvest. And a terrible fate awaited those who defied him. Da made sure that several strands of wheat, known as the “Pooka's share,” were always left in every field. Michael thought it extravagant to leave so much food for the crows to eat, but he could never convince his father of that.

As Da guided the horse out of the field and onto the road, he glanced back and saw Dermot hacking at the wheat. “Will you look at the fury in him?” he said, shaking his head in dismay. “Sure you’d think he was attackin’ the devil himself.”

Michael would never say so, but he agreed with his father. For as long as he could remember, Dermot had always been angry. He didn’t know why, but he was, and Michael had just learned to live with it.

“Ah, go easy on him.”

“Don’t you be tellin’ me how to deal with me own son.”

Michael fell silent. He didn’t want to upset his father any more than he already was. Especially today. Until this moment he’d told no one about his plans to go to America, not even Dermot. But tonight he would announce his plans to the family.

Michael looked up at the low clouds rolling in from the west. “Looks like more rain,” he said, changing the subject.

Da squinted at the sky and his brow furrowed with unease. “In all me years I can’t remember a wetter summer.” He flicked the reins and the horse picked up the pace. “It’s a black sign and that’s a fact.”

The village of Ballyross was essentially an afterthought. Lying almost in the center of a wide sweeping valley dominated by mountains checker-boarded with stone-walled fields, it had once been nothing more than a crossroads dissecting the valley. Then, an enterprising miller set up a grinding mill next to a swift flowing river. Soon a general store appeared across the road to sell to the people who sold their wheat to the miller. Then a grog shop appeared to quench the thirst of all those buyers and sellers. Then a Catholic church sprang up to save the souls of farmers bent on swimming to hell on a river of drink. Not to be outdone, a Protestant church with an even higher steeple appeared at the other end of the road to tend the souls of the Protestant gentry and protect them from the drunken papist bastards. One by one more tradesmen appeared to satisfy the needs of the growing community and, before anyone knew what was happening, Ballyross was a full-blown village.

Michael was carrying a sack of flour out of the general store when he saw Lord Somerville’s gleaming black landau coming up the road from the train station. He stopped to admire the graceful carriage with the Somerville coat of arms emblazoned on the door in gold leaf lettering. As the landau passed, he caught a glimpse of a young woman inside and sucked in his breath. She brushed an errant lock of auburn hair away from her forehead and glanced at him—or rather through him. Michael had never seen anyone more beautiful in his entire life.

“Who’s that, Da?”

“Young Emily. She’s been called home.”

Michael vaguely remembered a little girl with freckles who used to play in the Manor House garden. She’d gone away a long time ago and Michael had forgotten all about her. “Little Emmy?”

“Mistress Emily to you, me boyo.”

Michael watched the carriage disappear into a cloud of dust and felt an odd stirring within him.

Da saw the expression on his son’s face and felt a sudden press of dread. “Get any thought of her out of yer head, Michael. She’s not for the likes of you.”

Michael slammed the sack into the back of the wagon. “And why not? Because she’s the landlord’s daughter and I’m just a tenant farmer?”

“Never you mind,” Da said, frightened by that kind of talk. A man who didn’t know his place was bound for trouble. “Go fetch that other sack.”

Michael stomped back into the store, leaving Da to wonder, once again, what was the matter with the young people today.

The sprawling Somerville estates, less than two miles outside the village of Ballyross, had been home to six generations of Somervilles since the first Somerville, Lord Thomas, arrived in Ireland at the turn of the eighteenth century. Over the years, succeeding generations of Somervilles had occupied the house, adding extensions to the original Georgian mansion until it had become a majestic example of architectural eclecticism that was admired throughout the west of Ireland.

The carriage turned onto a long, well manicured road leading up to the manor house. Emily, her face a mask of resignation, stared at the imposing home perched on the crest of a long, sloping hill. It had been ten years since she’d last seen it and nothing, it appeared, had changed in that time. The tall, majestic oak tree she’d swung from as a little girl was still there. So, too, was the hill where she’d rolled snowballs until they were giant rounds of snow taller than she. The gate she’d swung on—and broken more than once—was still there, freshly painted and in good repair. This had been her home once, a place she loved. Now it was to be her prison.

As the carriage wheels crunched to a stop on the freshly raked gravel driveway, the front doors opened and a short, stout woman came rushing out. Nora, the family’s retainer for over fifty years, rubbed her hands on her apron expectantly as Emily stepped out of the carriage.

“For the love of God will you look at you,” Nora said, beaming. “You’re all grown up, Emmy— I mean, Miss Emily.”

Emily hugged Nora, genuinely glad to see the old housekeeper. “Well, I should hope so, Nora. It’s been ten years.”

“Did you have a good trip then?”

“As well as can be expected.”

Nora heard the strain in the young woman’s voice and nervously rubbed her hands in her apron. “Well, I’m glad you’re home safe just the same.”

Emily glanced toward the front door and stiffened.

A tall, ramrod straight figure with thick white hair and bushy eyebrows, partially concealing intelligent gray eyes, stood in the door. He flashed a hesitant smile and came down the steps toward her.

“Welcome, Emily.”

Emily made no move toward him. “Hello, Father.”

Somerville stopped as though he’d been slapped in the face. Self-consciously, he cleared his throat and clasped his hands behind his back.

Nora pulled her shawl around her, as though feeling a sudden chill. “Well, don’t be standin’ there gawkin’,” she snapped at two young servant girls, who were indeed gawking at the beautiful young woman standing before them. “Get the bags into the house.” She averted her eyes from her embarrassed master and took Emily’s arm. “Come inside, child. You’ll catch your death out here.”

The manor’s great room was indeed great—in size and in the splendor of its furnishings. Heavy tapestries of finely weaved patterns hung from walls covered with burgundy and sage green wallpaper imported from the Far East. Massive Oriental rugs added a touch of much needed warmth to the cold flagstone floors. Plush couches and armchairs, built by the finest furniture makers in Dublin and London, filled the room. Perched on delicat

ely wrought tables were collections of screens, fans, and porcelain and lacquer figures from China. Two huge Waterford chandeliers, hanging from chains attached to the wood beamed ceilings above, cast a soft warm glow to the otherwise cold room.

The fireplace, with ornate basket grates as tall as a man covering the opening, was the focal point of the room. Lord Somerville was standing at the fireplace warming his hands when Emily came in.

“You wanted to see me, Father?”

Somerville turned to look at his daughter and caught his breath. She’d taken off her bonnet and traveling coat and he was getting his first good look at her in ten years. She looked so much like her mother that it was unnerving. She had the same flowing auburn hair, the same intelligent green eyes. And she was the same age—twenty—when he’d married her mother. Somerville tried to push the thought of his dead wife out of his mind, but it was no use. She was always with him. Even after all this time, he still couldn’t think of her without heart-numbing grief.

“I trust your trip was uneventful?”

“What does it matter?” Her tone was icy. “I’m here, aren’t I?”

Ignoring the sarcasm in her tone, he said, “Perhaps you should take a nap. You must be tired from your long journey.”

“I’m not a child. I don’t take naps anymore.” Emily started toward the door. “Is Shannon still here?”

“Yes, but he’s getting old and cantankerous. I don’t think you should—” He didn’t finish the sentence because she’d already gone. Alone, once again, Somerville turned back to the fire and glumly poked at a log.

Fear

Fear Plague

Plague BZRK: Apocalypse

BZRK: Apocalypse Bzrk

Bzrk Love Sucks and Then You Die

Love Sucks and Then You Die Silver Stars

Silver Stars The Key

The Key Front Lines

Front Lines BZRK Origins

BZRK Origins Monster

Monster Gone

Gone The Snake

The Snake The Power

The Power Hunger

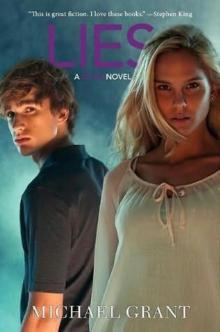

Hunger Lies

Lies A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Messenger of Fear

Messenger of Fear Eve & Adam

Eve & Adam The Trap

The Trap Light

Light An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam

An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam The Call

The Call Hero

Hero Soldier Girls in Action

Soldier Girls in Action Purple Hearts

Purple Hearts The Tattooed Heart

The Tattooed Heart The Fall of the Roman Empire

The Fall of the Roman Empire BZRK Reloaded

BZRK Reloaded Messenger of Fear Novella #1

Messenger of Fear Novella #1 The Magnificent 12

The Magnificent 12 Fear: A Gone Novel

Fear: A Gone Novel Villain

Villain Manhattan

Manhattan Eve and Adam

Eve and Adam Plague: A Gone Novel

Plague: A Gone Novel Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises In the Time of Famine

In the Time of Famine Hunger_A Gone Novel

Hunger_A Gone Novel Lies g-3

Lies g-3