- Home

- Michael Grant

Gone Page 4

Gone Read online

Page 4

“Hey, up there,” Sam yelled. “Kid. Can you get to the door or the window?”

He stared up, craning his neck. There were six windows on the front of the building upstairs, one in the alley. The far left window was where the fire was, but now smoke was drifting out of the second window, too. The fire was spreading.

“Mommy!” the voice cried. It was a clear voice, not choking from the smoke. Not yet.

“If you’re going in there, wrap this around your face.” Somehow Astrid had come up with a wet cloth, borrowed from someone and soaked.

“Did I say I was going in there?” Sam asked.

“Don’t get hurt,” Astrid said.

“Good advice,” Sam said dryly, and wrapped the wet fabric around his head, over his mouth and nose.

She grabbed his arm. “Look, Sam, it’s not fire that kills people, it’s smoke. If you get too much smoke, your lungs will swell up, they’ll fill with fluid.”

“How much is too much?” he asked, his voice muffled by the cloth.

Astrid smiled. “I don’t know everything, Sam.”

Sam wanted to take her hand. He was scared. He needed someone to lend him some courage. He wanted to take her hand. But this wasn’t the time. So he managed a shaky smile and said, “Here goes.”

“Go for it, Sam,” a voice yelled in encouragement. There was a ragged chorus of cheers from the crowd.

The entrance to the building was unlocked. Inside were mailboxes, a back door to the flower shop, a dark, narrow stairway heading up.

Sam almost made it to the top of the stairs before he ran into an opaque wall of swirling smoke. The wet cloth did nothing. One breath and he was on his knees, choking and gagging. Tears filled his stinging eyes.

He crouched low and found more air. “Kid, can you hear me?” he rasped. “Yell, I need to hear you.”

The “Mommy” was faint this time, from down the hall to the left, halfway to the other side of the building. Maybe the kid would jump out the window into someone’s arms, Sam told himself. It would be stupid to get himself killed if the kid could just jump.

The stink of the smoke was intolerable, awful, everywhere. It had a sourness to it, like smoke plus curdled milk.

Sam stayed on his knees and crawled down the hallway. It was strange. Eerie. The ratty hall runner below him seemed so normal: faded Oriental pattern, frayed edges, a few crumbs, and a dead roach. An overhead lightbulb was on, filtering pale light down through the ominous gray.

The smoke was swirling slowly lower, pressing down on him, forcing him lower and lower to find air.

There had to be six or seven apartments. No way to know which was the right one, the kid wasn’t yelling anymore. But the apartment on fire was probably the one just to his right. Smoke was shooting out from below that door, thick, fast, and furious as a mountain stream. He had seconds, not minutes.

He rolled onto his back. The smoke pouring from under the door was like a waterfall in reverse, falling upward in a cascade. He kicked at the door, but it was no good. The lock was higher up; all his kick did was rattle the door. To break it open he would have to stand up, straight into that killing smoke.

He was scared. And he was mad, too. Where were the people who were supposed to do this? Where were the adults? Why was this up to him? He was just a kid. And why hadn’t anyone else been crazy enough, stupid enough to rush into a burning building?

He was mad at all of them and, if Quinn was right and this was something God had done, then he was mad at God, too.

But if Sam had done this…if Sam had made all this happen…then there was no one to be mad at but himself.

He took in all the breath he could manage, jumped to his feet, and slammed against the door all in one frantic motion.

Nothing.

And slammed again.

Nothing.

And again, and he had to breathe now, he had to, but the smoke was everywhere, in his nose, his eyes, blinding him. Again and the door opened and he fell in and hit the floor, facedown.

The smoke trapped in the room erupted into the hallway, exploded out like a lion escaping its cage. For a few seconds there was a layer of breathable air at floor level and Sam took in a breath. He had to fight to keep from coughing it back out. If he did that, he was going to die, he knew it.

And for just a second it was partly clear in the apartment. Like a break in the clouds that gives you a little tease of clear blue sky before drawing the dark curtain once more.

The kid was on the floor, gagging, coughing, just a little kid, a girl, maybe five at most.

“I’m here,” Sam said in his strangled voice.

He must have looked terrifying. A big shape wreathed in smoke, face covered, black soot in his hair, smearing his skin.

He must have looked like a monster. That was the only explanation. Because the little girl, the terrified, panicky little girl, raised both of her hands, palms out, and from those chubby little hands came a blast, an explosion, jets of pure flame.

Flame. Shooting out of her tiny hands.

Flame!

Aimed at him.

The blast narrowly missed Sam. It passed his head with a whoosh and hit the wall behind him. It was like napalm, jellied gasoline, liquid fire that stuck to the wall where it hit and burned with mad intensity.

For a second he could only stare, frozen in amazement.

Insane.

Impossible.

The little girl cried out in terror and raised her hands again. This time she wouldn’t miss.

This time she would kill him.

Not thinking, just reacting, Sam extended his arm, palm out. There was a flash of light, bright as an exploding star.

The kid fell on her back.

Sam crawled to her, shaking, stomach clenched, wanting to scream, thinking, no, no, no, no.

He scooped the kid into his arms, afraid she would wake up, and afraid that she wouldn’t. He stood up.

The wall to his right fell in with a sound like ripping cardboard. Plaster was falling away, revealing the wall’s structure, the lathe boards and two-by-fours. The fire was inside the wall.

A blast of heat, like opening an oven, staggered Sam. Astrid had said it wasn’t the fire that killed you. Well, she hadn’t seen this fire, or guessed that a little kid could shoot flame from her hands.

Sam held the child in his arms. Fire to his back and to his right, crisping his eyelashes, baking his flesh.

A window straight ahead.

He stumbled forward. He dropped the kid like a sack of dirt and slammed the window up with both hands. Smoke roiled around him, the fire chasing it toward this fresh source of oxygen.

Sam felt in the gloom for the child and found her. He lifted her, and there, miraculously, was a pair of hands waiting to take the kid. Hands reaching through the smoke, seeming almost supernatural.

Sam collapsed against the sill, half hanging out of the window, and someone grabbed him, and dragged and slid him down the aluminum ladder. His head smacked the rungs and he did not mind one tiny bit because out here was light and air and through squinting, weeping eyes he could see the blue sky.

Edilio and a kid named Joel manhandled Sam down to the sidewalk.

Someone sprayed him with a hose. Did they think he was on fire?

Was he on fire?

He opened his mouth and gulped greedily at the cold water. It washed over his face.

But he couldn’t hold on to consciousness. He floated away. Floated on his back on gentle surf.

His mother was there. She was sitting on the water just beside him. Her chin rested on her knees. She wasn’t looking at him.

“What?” he said to her.

“It smelled like fried chicken,” she said.

“What?” he said.

His mother reached over and slapped him hard across the face.

His eyes flew open.

“Sorry,” Astrid said. “I needed to wake you up.”

She knelt beside him and placed somethi

ng against his mouth. A plastic mask. Oxygen.

He coughed, and breathed. He pulled the mask away and threw up, right on the sidewalk, doubled over like a drunk in an alleyway.

Astrid looked away discreetly. Later he would be embarrassed. Right now he was just glad to be able to throw up.

He breathed more oxygen.

Quinn was holding the garden hose. Edilio was racing to hook one of the bigger fire hoses up to the hydrant. There was a trickle, then, as Edilio worked the long-handled wrench and opened the hydrant all the way, a gusher. The kids on the other end had to wrestle the hose like they were fighting a python. It would have been funny some other time.

Sam sat up. He still couldn’t talk.

He nodded to where half a dozen kids knelt around the little firestarter. She was black, black by race and from the coating of soot. Her hair was gone on one side, burned away. On the other side she had a little girl’s pigtail held with a pink scrunchy.

Sam knew from the reverential way the kids knelt there. He knew, but he had to ask, anyway. His voice was a soft croak.

Astrid shook her head. “I’m sorry, Sam,” she said.

Sam nodded.

“Her parents probably had the stove on when they disappeared,” Astrid said. “That’s most likely what caused the fire. Or maybe a cigarette.”

No, Sam thought. No, that wasn’t it.

The little girl had the power. She had the power Sam had, at least something like it.

The power he had used in panic to create an impossible light.

The power he had used once and almost killed someone with.

The power he had just used again, dooming the very person he was trying so hard to save.

He was not the only one. He was not the only freak. There was—or had been—at least one other.

Somehow, that realization was not comforting.

FIVE

291 HOURS, 07 MINUTES

NIGHT CAME TO Perdido Beach.

The streetlights turned on automatically, doing little to push back the darkness, doing a lot to cast deep shadows on frightened faces.

Close to a hundred kids milled around the plaza. Everyone seemed to have a candy bar and a soda. The little store, the one that sold mostly beer and corn chips, had been looted. Sam had snagged a PayDay and a Dr Pepper. The Reese’s and Twix and Snickers were all gone by the time he got there. He’d left two dollars on the counter as payment. The money was gone within seconds.

The apartment building had burned half away before the fire had run out of energy. The roof had collapsed. Half the upper floor was gone. The ground floor looked like it would survive, though the shop windows were smoke-blackened on the inside. Smoke rose now in tendrils, not billows, and the stench was everywhere.

But the hardware store and the day care had been saved.

The body of the little girl still lay on the sidewalk. Someone had put a blanket over her. Sam was grateful for that.

Sam and Quinn sat on the grass, toward the center of the plaza, near the dead fountain. Quinn rocked back and forth, hugging his knees.

Bouncing Bette came over and stood awkwardly in front of Sam. She had her little brother with her. “Sam, do you think it’s safe to go to my house? We have to get something.”

Sam shrugged. “Bette, I don’t know any more than you do.”

Bette nodded, hesitated, and walked away.

All the park benches were taken. Some little family units draped sheets over the few benches, making limp pup tents. Many kids went home to their empty houses, but others needed people around them. Some found comfort in the crowd. Some just needed to see what was going on.

Two kids Sam didn’t know, probably fifth graders, came up and said, “Do you know what’s going to happen?”

Sam shook his head. “No, guys, I don’t.”

“Well, what should we do?”

“I guess just hang out for a while, you know?”

“Hang out here, you mean?”

“Or else go to your house. Sleep in your own bed. Whatever feels right.”

“We’re not scared or anything.”

“You’re not?” Sam asked dubiously. “I’m so scared, I wet myself.”

One kid grinned. “No, you didn’t.”

“Nah. You’re right. But it’s okay to be scared, man. Every single person here is scared.”

It was happening a lot. Kids coming to Sam, asking him questions for which he had no answers.

He wished they would stop.

Orc and his friends dragged lawn chairs out of the hardware store and set themselves up right in the middle of what had once been Perdido Beach’s busiest intersection. They were just beneath the stoplight, which continued changing from green to yellow to red.

Howard was berating some lower-ranking toady who had lit a Prest-O log and was trying to get it to grow into a bonfire. Orc’s crew brought a couple of wood axe handles and wooden baseball bats out of the hardware store and tried unsuccessfully to burn them.

They also carried metal bats and small sledgehammers from the hardware store. Those they kept.

Sam didn’t bring up the little girl, the way she was just lying there. If he brought it up, then it would become his job to do something. To dig a grave and bury her. To read the Bible or say words. He didn’t even know her name. No one seemed to.

“I can’t find him.” It was Astrid, reappearing after an absence of at least an hour. She had gone to hunt for her little brother. “Petey’s not here. Nobody has seen him.”

Sam handed her a soda. “Here. I paid for it. Tried to, anyway.”

“I don’t usually drink this stuff.”

“You see any ‘usually’ around here?” Quinn snapped.

Quinn didn’t look at her. His eyes were restless, going from person to person, thing to thing, like a nervous bird, never making direct eye contact. He looked strangely naked without his shades and fedora.

Sam was worried about him. Of the two of them, it was Sam who was usually too serious.

Astrid let Quinn’s rudeness slide and said, “Thanks, Sam.” She drank half the can but didn’t sit down. “Kids are saying it’s some military thing gone wrong. Or else terrorists. Or aliens. Or God. Lots of theories. No answers.”

“Do you even believe in God?” Quinn demanded. He was looking for an argument.

“Yes, I do,” Astrid said. “I just don’t believe in the kind of God who disappears people for no reason. God is supposed to be love. This doesn’t look like love.”

“It looks like the world’s worst picnic,” Sam said.

“I believe that’s what’s called gallows humor,” Astrid said. Noticing Sam and Quinn’s blank looks, she said, “Sorry. I have this annoying tendency to analyze what people say. You’ll either get used to it or decide you can’t stand me.”

“I’m leaning toward the second choice,” Quinn muttered.

Sam said, “What’s gallows humor?”

“Gallows, as in, what they hang people from. Sometimes when people are nervous or afraid, they make jokes.” Then she added, a bit ruefully, “Of course, some people, when they’re nervous or afraid, turn pedantic. And if you don’t know what pedantic means, here’s a clue: in the dictionary, I’m the illustration they use.”

Sam laughed.

A little boy no more than five years old and carrying a sad-eyed gray teddy bear came over. “Do you know where my mom is?”

“No, little man, I’m sorry,” Sam said.

“Can you call her on the telephone?” His voice trembled.

“The phones don’t work,” Sam said.

“Nothing works,” Quinn snapped. “Nothing works and we’re all alone here.”

“You know what I bet?” Sam asked the boy. “I’ll bet they have cookies at the day care. It’s right across the street. See?”

“I’m not supposed to cross the street.”

“It’s okay. I’ll watch while you do, okay?”

The little boy stifled a sob, then walke

d off toward the day care, clutching his bear.

Astrid said, “Kids come to you, Sam. They’re looking to you to do something.”

“Do what? All I can do is suggest they eat a cookie,” Sam said, with too much heat in his tone.

“Save them, Sam,” Quinn said bitterly. “Save them all.”

“They’re all scared, like us,” Astrid said. “There’s no one in charge, no one telling people what to do. They sense you’re a leader, Sam. They look to you.”

“I’m not a leader of anything. I’m as scared as they are. I’m as lost as they are.”

“You knew what to do when the apartment was burning,” Astrid said.

Sam jumped to his feet. It was just nervous energy, but the movement drew the gaze of dozens of kids nearby. All looking at him like he was going to do something. Sam felt a knot in his stomach. Even Quinn was looking at him expectantly.

Sam cursed under his breath. Then, in a voice just loud enough to carry a few feet, he said, “Look, all we have to do is hang tight. Someone is going to figure out what’s happened and come find us, okay? So everyone just chill, don’t do anything crazy, help each other out and try to be brave.”

To Sam’s amazement he heard a ripple of voices repeating what he’d said, passing it on like it was some brilliant remark.

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” Astrid whispered.

“What?”

“It’s what President Roosevelt said when the whole country was scared because of the Great Depression,” Astrid explained.

“You know,” Quinn said, “the one good thing about this was that I got away from history class. Now history class is following me.”

Sam laughed. Not much, but it was a relief to hear that Quinn still had a sense of humor.

“I have to find my brother,” Astrid said.

“Where else could he be?” Sam asked.

Astrid shrugged helplessly. She looked cold in her thin blouse. Sam wished he had a jacket to offer her. “With my parents somewhere. The most likely places are where my dad works or else where my mom plays tennis. Clifftop.”

Clifftop was the resort hotel just above Sam’s favorite surfing beach. He’d never been inside or even on the grounds.

Fear

Fear Plague

Plague BZRK: Apocalypse

BZRK: Apocalypse Bzrk

Bzrk Love Sucks and Then You Die

Love Sucks and Then You Die Silver Stars

Silver Stars The Key

The Key Front Lines

Front Lines BZRK Origins

BZRK Origins Monster

Monster Gone

Gone The Snake

The Snake The Power

The Power Hunger

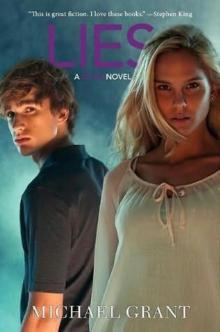

Hunger Lies

Lies A Sudden Death in Cyprus

A Sudden Death in Cyprus Messenger of Fear

Messenger of Fear Eve & Adam

Eve & Adam The Trap

The Trap Light

Light An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam

An Artful Assassin in Amsterdam The Call

The Call Hero

Hero Soldier Girls in Action

Soldier Girls in Action Purple Hearts

Purple Hearts The Tattooed Heart

The Tattooed Heart The Fall of the Roman Empire

The Fall of the Roman Empire BZRK Reloaded

BZRK Reloaded Messenger of Fear Novella #1

Messenger of Fear Novella #1 The Magnificent 12

The Magnificent 12 Fear: A Gone Novel

Fear: A Gone Novel Villain

Villain Manhattan

Manhattan Eve and Adam

Eve and Adam Plague: A Gone Novel

Plague: A Gone Novel Fergie Rises

Fergie Rises In the Time of Famine

In the Time of Famine Hunger_A Gone Novel

Hunger_A Gone Novel Lies g-3

Lies g-3